The Gundestrup Cauldron - Mythology

and Cosmology

The Native Way of

understanding Cosmos

Gundestrup Cauldron Peat bog, Gundestrup

(Denmark) First century B.C.E. Silver partially gilded. Diameter

69cm., Height 42cm.Copenhagen, Nationalmuseet.

The Gundestrup Cauldron is a religious vessel

found in Himmerland, Denmark, 1891. It was deposited in a dry section of

a peat bog, dismantled with its five long rectangular plates, seven

short ones and one round plate. Each plate is made of 97.0% pure silver

and filled with various motifs of animals, plants and pagan deities.

Sophius Müller(1892) reconstructed these plates into the present form of

the cauldron: five rectangular plates are placed in the inside of the

cauldron leaving 2cm of space between each, and the seven (originally

eight) plates form the outside of the cauldron. The round plate is

assumed as the base of the cauldron. The reconstructed cauldron with its

spherical base and cylindrical side is 69cm. in diameter and 42cm. high;

both the inner and outer plates are almost of the same height ( about

21cm) forming the cylindrical side of the cauldron.

As the largest surviving piece

of Europian Iron Age silver work, the Gundestrup Cauldron has been given a

special interest by many scholars. Especially, its high quality

workmanship and iconographic variety have generated an incessant inquiry

into the origin of the cauldron. Though the date of the cauldron is

generally attributed to the 2nd or 1st century BCE

(La Tène III), there still remains much room for controversy concerning

the place of its manufacture. The main problem comes from the fact that

its style and workmanship is Thracian rather than Celtic despite its

decorative motifs manifestly Celtic. So far, scholastic opinions have been

largely divided into two groups: those who argue for the Gaulish origin

and those who argue for the Thracian origin. The former locate the

manufacture of the cauldron in the Celtic west while the latter opt for

the Lower Danube in southeastern Europe.

The Vessel

The whole vessel represents the Whole World

as known from the ancient 3 World division and dimension of Earth, the

nearest Celestial World and the farthest celestial world of the Milky

Way.

- Maybe the Vessel also once have had a lid

in order to show some details regarding "the top" of these 3 Worlds? In

that case the imagery would have shown some mythological "world axis"

imagery.

Interpretation

In Norse Mythology these 3 worlds is

mentioned: Midgaard for the humans; Asgaard for the nearest celestial

world where the Sun, the Moon, the (5) Planets and for the Star

Constellations and Udgaard (Out-Yard) for the farthest world

representing the Milky Way galaxy where the Giants (Jaetter) live.

The interactive Mytho-Cosmological plays

between these 3 worlds must be incorporated in the telling of vessel

imagery. That is: We are dealing with the cosmological creative and

interactive forces in these 3 worlds and we are also dealing with the

Mytho-Cosmological geographical and celestial locations of these 3

worlds.

- Some knowledge would be of an obvious

physical character as for instants day and night observations and the

Seasons, and even the immediate knowledge of the "Udgaard",

the Giant Milky

Way contours. But the fully knowledge beyond the Milky Way, could only have been

collected by spiritual means i.e. by Shaman travelling gathering

intuitive, non verbal knowledge. It is the intuitive travelling

knowledge "beyond" the Milky Way, that is incorporated in the Worlds

Creation Myths.

The Plates

- The Base: A Bull in the center. A Woman

with a Sword, Bull and 2 Dogs

- 5 inner plates.

- 7 outer.

- The plates on the outside show

4

male and 3 female busts.

- (Maybe there once also was a Lid?)

The Base

In the Norse Mythology Creation Story,

http://www.native-science.net/Creation.Myth.Norse.htm the Giant

Audhumbla Cow/Bull, located in the southwards warmer and lighter

Muspelheim, "licked forward" the Milky Way Giant of Ymir,

the northern hemisphere Milky Way figure.

The logical choice of a Bull/Cow comes from

combining the Bull's roar with the thundering sound of creation in the

Milky Way galaxy center. And of course when also choosing a Cow and the

Utter milky symbols, this gives the natural associations to nourishing

and to the white river of the Milky Way and thereby building op the the

telling of how all life once began in the center of our galaxy.

On this base plate, the Bull/Cow is centered

southwards as in the Milky Way center in the Star Constellation of

Sagittarius, and Ymir is hovering above as the northern Milky Way

contours on the Northern Earth night hemisphere. (A physical observable

symbol)

http://www.native-science.net/MilkyWay.GreatestGod.htm

Inner Plate A

This plate shows a variety of animals

around the horned figure in the center. The horned figure is presented

with his legs folded and wears a torque around his neck. he holds

another torque in his right hand and a horned serpent in his left hand.

This torque-wearing god with stag antlers is generally identified as the

Celtic god, Cernunnos. Cernunnnos is the Lord of the animals and the

torques he wears are the symbols of wealth and prosperity. Cernunnos was

first recognized by the inscription of the Paris

monument which, along with the inscription, shows a horned deity

wearing torques on his antlers. Because of this antlered deity, this

plate has often been cited by those who argue for the Gaulish origin.

However, this general identification of the central figure with

Cernunnos has been challenged by some scholars. As early as 1971, Powell

noted that there is no ground for believing that every Celtic horned god

should be called "Cernunnos depending solely upon the defective

inscription in Paris. In agreement with Powell, Olmsted(1979) suggests

that the figure be classified as "Dieu Accroupi." According to him, all

of the "accroupi" figures with antlers, torques and serpent come from

north central Gaul, while only a quarter of the "accroupi" figures with

one or two attributes come from outside the region.

Apart from the identity of the horned

deity, it is recognized, however, that the posture and dress of the

figure are not necessarily Celtic. His folded legs seen from above hint

at the possible link with Buddhism in the East and his costume -

tight-fitting breeches and coat fastened by a belt at the waist - is

often matched by the costumes of horse-riding races from southeastern

Europe. More recently, Anders Bergquist found that the shoes of the

deity with zig-zag bindings are exactly the same type as those found in

Thracian silver repoussé from Sãlistea and

Durentsi.

His discovery seems to confirm the eastern influence on the Gundestrup Cauldron for no such examples have been found in the Celtic West.

Although, as in the identification of the

central figure, scholars have difficulties in identifying some animals

surrounding the central figure, it is generally accepted that beside him

on the left and right are a hound and a stag. On the back of the stag is

depicted a bull which repeats itself on the upper left corner of the

plate. The bull on the left is followed by two other animals: a dolphin

with a rider and a lion. However, the identities of these animals have

been occasionally refuted. For example, Powell argues that the dolphin

is actually a sturgeon. Also, the lion right behind the dophin is

identified as a boar by some scholars. Finally, a confronted pair of

animals in the lower left part of the plate are generally considered as

lions. These diverse animals are given special interest by those who

argue for the Thracian manufacture of the cauldron. Powell claims that

the stag and bulls have the "stolid look" that seems to have come from

eastern Europe and that the confronted pair of lions are typically

oriental.

Concerning the iconography of the plate,

many scholars assume that the plate has a coherent narrative. Klindt

Jensen notes that the eyes of the three figures- Cernunnos, the stag,

and the hound- are level, thus suggesting a striking connection between

them. Most notably, Olmsted identifies the central figure as a Gaulish

prototype of later Irish Cú Chulainn in Táin and reads the whole

plate as a combination of episodes from the same tale. According to him,

the sequence of the three figures on the upper left corner describes the

various transformations (shape-shifting) of the two Irish bulls: Donn

Cuailnge and Finnbennach. He calls attention to the fact that the

sequence of animal transformations ending in the two bulls occurs in the

same order in both the tale and the plate.

(Paris Cernunnos)

Interpretation:

When one observe a man riding on a Dolphin,

one cannot possibly think of a scene of Earth. This stage is not set and

played out in the human Norse Midgaard area. The dear-horned younger man hold

the Torque symbol of Life in his right hand, and also around his neck,

and the Serpent symbol of creation in his left.

Inner Plate B

This plate shows an antithetical

arrangement of animals around a bust of a goddess. The goddess is

presented in the center with a six-spoked rosette wheel on either side

of her. She is flanked by two elephants confronting each other. Below

them are two griffins arranged in the same antithetical manner and a

hound is placed in the lower center of the plate, between these two

griffins. The goddess seems almost identical with the goddess on

plate

(g): she has S-curve hair strands and curvilinear eye-ridges forming

a T-shape with her nose. The rendering of her arms is also similar to

that on

plate (e). Though it is not certain that the six-pointed wheels

represent a wagon, the goddess is usually interpreted as riding a wagon.

Actually, a chariot is often represented by a single wheel of the same

type in Gaulish coinage. Olmsted suggests that the presence of the

elephants on either side of the wagon could have resulted from the

influences of the Roman coinage which portrays elephants pulling a

chariot. Olmsted also identifies her with the Celtic Goddess Medb. She

is a god of war and rulership; diverse animals and the chariot represent

her war-like nature as a territory goddess.

Though elephants are also depicted in the

Celtic west, the fantastic characters of the animals are often explained

in the oriental context. Especially the griffins with their segmented

wings and rounded bird heads are similar in concept to those imaginary

animals often observed in

Thracian

metal works (Phalerae). Even the elephants suggest an oriental

influence. Olmsted notes that the elephant is less a manifestation of

the actual animal than a synthetic creature incorporating diverse parts

of other animals: the body of the elephant shows the rear leg and tail

of the bull on the

plate

(D) and the trunk of the lion on the

plate

(C). Its head is also same as that of the bull except its trunk,

clumsily added to the head. Thracian characters of the animals are more

clear in their hanging feet: the feet of the griffins are literally

hanging in midair, not wearing any weight of the body. The bodies of

these animals are decorated with interspersed large and small dots and

lines. This also can be read in the context of Thracian workmanship for

the decorative techniques of hatching and punch marks are characteristic

of Thracian silver smithing.

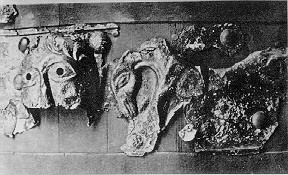

(Phalera from

Stara Zagora) (Phalera from

Stara Zagora)

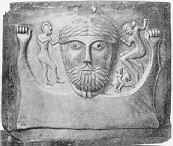

Inner Plate C

This plate shows an intriguing iconography

of two deities with a broken wheel: in the center of the plate, a bust

of a bearded deity is depicted with a half-shaped wheel on his right

side and a full-length leaping figure is holding the rim of the wheel

from the right. Under this leaping figure, a horned serpent is

presented. The rest of animals are placed clockwise around this group of

two deities: in the upper part of the plate, two identical beasts are

depicted on either side of the group, both facing the left side of the

deities and in the lower part, three griffins are depicted in parallel,

all facing the right side of the deities. The space between the upper

and lower group of the animals is filled with some botanical patterns

which are usually identified as ivy tendrils.

The bust of a bearded god in the center is

almost identical with the small bust on the right shoulder of the

goddess on

plate

(e). On the other hand, the leaping figure holding the wheel on the

left is similar to the gods of the

plate

(A) and

(E)

in its size and dress. He wears tight fitting, short-sleeve clothes and

a horned helmet ending in knob like terminals. Drawn on these

similarities, Olmsted reconstructs the narrative of this plate in

relation to the other plates; according to him, the gods on plates (A),

(C), (E) are different representations of the same god, the Gaulish

version of Cú Chulainn in Irish tale Táin Bó Cuailnge. Like Cú Chulainn

in the Táin, the young god wearing the horned helmet uses a broken wheel

in confrontation with the bearded god, Fergus who, on plate (e),

accompanies the goddess sharing traits with Irish Medb. The horned

serpent under the feet of the young god can be read as the Irish goddess

Morrigan who, in another anecdote from the tale, disguised herself in

the shape of an eel and finally had her ribs crushed under the feet of

Cú Chulainn.

Indeed, the unique presence of a broken

wheel suggests that this plate may be a description of a particular

narrative. Yet, there is no guarantee that this half shaped wheel was

meant to be a broken wheel. Ellis Davidson notes that the wheel was a

familiar Scandinavian symbol in the period of the late Bronze Age, a

basic motif in the rock carvings which continued to appear throughout

the Iron Age. On the other hand, some scholars identify the bearded

deity with Jupiter Taranis of the Celts whose traits are wheels.

Besides, Olmsted fails to explain the existence of the fantastic animals

such as lions(?) and griffins. Even if we accept his argument that the

beasts in the upper part of the plate are variants of the wolf, the

griffins are completely inexplicable in the context of the Irish tale,

Táin, for griffins are unknown in early Irish tradition. Actually, these

griffins are all the same with their segmented wings, rounded bird heads

and hanging feet as those on

plate

(B). As manifest examples of Thracian style, they are often compared

with the fantastic animals of Sark, Helden, Paris phalerae of Thracian

origin and the Agighiol vase (belonging to 4th BC Thracian

style). Especially the

Agighiol

vase shows the parallel expressions of the hanging feet depicted on

plate (B) and (C): the deer with their legs dangling in midair as well

as griffins and lions.

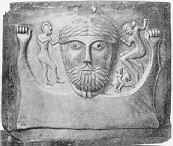

(Agighiol Vase)

(Agighiol Vase)

Inner Plate D

This plate is generally interpreted as a

bull-slaying scene. Three bulls are placed in a horizontal line, facing

the same direction. They have massive, ham-like rumps and short but

thick necks which resemble those of a bull on the

Sark

phalerae. Focusing on their shape and hatching patterns of the

bodies, Powell traces their origin back to Anatolian and earlier

Urartian tradition. On the lower right side of each bull, a man is

standing in the posture of attacking the bull with a sword. Under the

feet of each bull, by the side of each man, a dog is depicted as running

toward the left while a cat-like creature is running in the same

direction over the back of the bull. These cats as well as the dogs have

the same hanging feet. As shown in other plates, the spaces between each

figure are filled with tear-drop shaped leaves.

The three fold composition of this plate is

often related with the Celtic triad in which the actions of heroes and

the slaying of monsters are set in groups of three. Here, the figures

are not completely identical; the middle man wears a jacket and the

other two do not. However, the basic concept of the composition seems to

have a strong connection with the Celtic tradition. Since all the bulls

and human figures are represented in a highly stylized, static,

monumental posture, Ellis Davidson concludes that the scene depicts a

ritual killing with "no attempt at realism."

Inner Plate E

Interpretation:

This plate is horizontally divided

in the middle by the Tree of Life.

On the left-most side of the plate, the

standing god wears what seems to be a pigtail or a tight-fitting knitted

cap with a tassel. He is much larger than the rest thus dominating the

whole scene. He holds a small man upside down over a bucket-shaped

object; he seems to be either plunging the man in the bucket or pulling

him out. Before the god, under the bucket, a dog is depicted in midair

as if leaping up. The rest of the scene is filled with two rows of

warriors vertically arranged along with the dividing stem of a tree in

between: the upper warriors are horse-riders and the lower warriors are

foot-warriors holding spears and shields. The last three men in the

lower row are blowing musical instruments which are safely identified as

the Celtic instrument, carnyx. Over the carnyx in the far right corner

is depicted a ram-headed serpent similar to that on

plate

(A).

Along with the plate (A), plate (E) is said

to be the most Celtic in its iconography because of the presence of the

carnyx. It consists of a long thin tube at the top of which is added

a boar’s head with jaws wide open and a projecting mane on the back. The

decorated helmets of the warriors in the upper row are also Celtic.

Here, we have five different types of helmets: one has a boar on top,

one a pair of crooked thin horns ending in knobs, one a crescent shape

with concave side down, one a bird with its wings folded. These helmets

with various adornment fit with Poseidonius’s description. Besides,

Olmsted notes that the weapons of the soldiers such as shields with

circular bosses are those of western and central Europe.

However, there are some details which are

not apparently Celtic. For example, the distinctive costumes of the men,

of the same type as those elsewhere on the bowl, are not characteristic

of Celtic Gaul, as Müller observed long ago. Most notably, the round

disc securing the straps on the horse is exactly the same type as an

iron phalera from southern Europe. Both discs consist of a round

central decoration surrounded by smaller circles at the circumference.

Based on this observation, Bergquist argues that it points to the

eastern origin of the cauldron: he quotes from Allen(1971: 24) that the

auxiliary horsemen of the Romans, many of whom came from Thrace rode on

horses "plentifully decked with phalerae" and that such cavalry are

possible agents of the transmission of the phalerae across Europe. Also,

the similar arrangement of figures and plant pattern is found in the

Thracian

helmet from Agighiol on which the horse riders are depicted in

parallel below the horizontal line of ivy pattern. (Bergquist and

Taylor:14)

Concerning the symbolic content of the

scene, quite a few interpretations have been made. The most widely

accepted one is that the scene portrays a ritual dipping and that the

bucket-shaped object is a cauldron of rebirth. This cauldron of rebirth

is associated with Celtic gods, particularly the Dagda in later Irish

literature. Since the scene depicts the warriors and the idea of the

dead being reborn into an after life is common to Celtic mythology, the

theme of rebirth seems quite convincing. In favor of this

interpretation, Ellis Davidson reads the dog and the horned serpent as

symbols of the Other world. On the other hand, Gricourt (1954) suggests

that the scene depicts the dead warriors marching in as spear men below

and riding away alive as horsemen above. However, there seems to be no

guarantee for his interpretation. Olmsted challenges this usual

interpretation by asking why the resurrected warriors rise in rank,

marching up as dead foot soldiers to ride off as horsemen after

resurrection. Furthermore Olmsted argues that the bucket shaped object

is not a cauldron and that the scene depicts a death by drowning which

is often found in Irish tales such as Aided Muirchertaig maic Erca and

Aided Diarmada. Another quite interesting interpretation is made by

Kimmig (1965). He suggests that the foot soldiers are carrying a tree

which is to be placed as a votive offering into one of the sacred pit

shafts which have been excavated on Celtic territory.

(Agighiol helmet)

The Outer plates show 4

male and 3 female busts.

Outer Plate a

Though many scholars since Müller believe that

there are at least two artists involved in the manufacture of the

cauldron, the outer plates share some basic characteristics. Most of

all, as Sandars points out, all the gods are represented in a static

posture and the scenes show almost symmetrical arrangements of the

figures. Other common features of the gods include the stylized or

patternized hair with the top of the head left bald, no ears, small

mouths, T-shaped line of eye brows and nose, and the insetting of eyes

with glass.

The basic iconographic concept of the outer

plates - arrangement of human busts around the cauldron - has been often

compared with that of

Rynkeby

cauldron and

Bavai

calendar vase from Belgium though the letter is assumed to post-date

the cauldron; it is assumed to be of the early Roman period. Recently,

Bergquist and Taylor suggest that the arrangement of the human bust may

indicate southeastern origin because faces are arranged around bowls in

Southeast Europe too. They also notes that human busts are often

observed in the later Thracian style metal works.

On plate (a), a bearded god holds a small

man in each hand over his shoulders. He is in so-called "orans

position"with his arms raised. Like another male god on

plate

(d), he doesn’t wear a torque; instead he has long whisker-like

strings. Each of the two men seems to hold a boar with one of their

arms. However, from a closer view, one can recognize that each one

reaches his hand upward to a boar and just touches it. The one on the

right has a dog below him while below that on the left is a horse with

wings, a so called "Pegasus." As shown in the inner plates, the

identifications of the scenes on outer plates have not been very

successful either. Olmsted, who reads the whole scene on the cauldron as

a manifestation of the Irish tale, Táin, identifies the central

god with Gaulish equivalent of Cú Rói who judges between the heroes in

the Irish myth. Here, according to his interpretation, the Gualish Cú

Rói judges the champions competing for the boar.

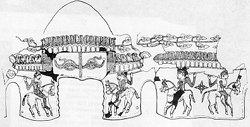

(Rynkeby Cauldron) (Bavai Vase)

Outer Plate b

Plate (b) shows a male deity holding two

sea horses or dragons. These two animals have the mixed characters of

horse and dragon; they have a long, serpentine body of a dragon and a

horse-like head and two front legs. Their ribs are prominently fluted

and the tails and wings are swirled. Below the god is a double-headed

monster attacking small figures of fallen men. This double headed

creature has been given a special interest by many scholars. Jacobsthal

associates it with the Early La Tène beast from Cuperly and a two headed

beast on a coin from the Jersey hoard. This monstrous figure, which

continued to appear until late in the Middle Ages, is also said to be an

animated fire-dog, representing the metal frame set frontally across the

fire on an open hearth, with bull or ram heads at either end.(Davidson:

498) A number of such fire-dogs have been recovered from rich Celtic

graves in England and on the Continent. Based on this interpretation,

Ellis Davidson assumes that the men reclining beside it are feasting

beside the hearth and that this iconography may indicate a possible link

between this deity and the Other World in the feast of which the dead

join their ancestors. On the other hand, as early as 1913, Hubert

suggested that this scene should be related to the sea or water since

the god holds the sea horses. As for the central god, he drew parallel

to the Welsh and Irish god of the sea and the other world: Manawydan and

Manannan. As an extension of Hubert's interpretation, Olmsted relates

the god to the Irish character Froech who fights with water monster in

Táin Bó Fraích.

Outer Plate c

This plates shows a deity with his upraised

hands in "orans position" as the other male gods on the outer plates.

However, unlike the others, his hands are empty. He has a boxing man at

his right and on the left is a leaping figure with a small horse rider

below it. The leaping figure is similar to the one on the

base

with his upturned queue of hair, which is also found in

plate

(g). The two men are dressed in the same type of garment as that

shown on the inner plates, a close fitting jacket or vest with tight

trousers ending at the knee. Since this kind of dress is commonly

observed in horse-riding races, there are no iconographic details

characteristically Celtic or Thracian on this plate. Hence, the depicted

scene has found no parallel either in Celtic mythologies or Thracian

image repertory.

Outer Plate d

The iconographic details of this plate are

comparatively clear: a bearded god is holding two stags in each hand.

Stylistically, this plate share some characteristics with the

plates

(e) and

(g):

all of them have a dotted background which ends in a zig-zag boundary at

the top of the plate and ivy tendrils which fill the empty spaces

between the figures. Since boars and stags were the major animals

revered by the Celts, one may argue for the Gaulish character of this

plate. But they were sacred animals also among the many other peoples of

central and southern Europe. Olmsted identifies the animals as deer and

the god as Gaulish equivalent of Irish Segamain, who is prominently

associated with deer. However, he admits that deer hunting is a common

feature in the saga literature.

Outer Plate e

Plate (e) shows a bust of a goddess in the

center and the smaller busts of two male gods on her shoulders. She

wears a torque and has a typical mask-like face with her small mouth and

T-shaped eye brows and nose. The bearded deity on her right shoulder is

almost identical with the central god on the inner

plate

(C) even in their round shaped pattern beneath their beard. They may

represent the same god in a different context or just two different

gods. If the former is the case, this means that the decoration program

of the cauldron is based on a certain kind of narrative or a group of

narratives and that each plate is interconnected with one another

iconographically. In favor of this view, Olmsted identifies the central

goddess with Irish Medb and the two gods with her husband Ail and her

lover Fergus. The tale says that because of her many sexual partners,

she "never had one man without another waiting in his shadow." Based on

this passage, Olmsted suggests that this scene may represent sexual

relationships of Medb. The background of the figures is dotted and

filled with ivy-tendrils as shown on the (d), (g).

Outer Plate f

Plate (f) shows an interesting iconography.

The central goddess holds a small bird in her upraised right hand while

her left arm is placed across her chest. Crossed over her left arm is

lying a small man and on the opposite side to the man is a dog upside

down. Some have suggested that the goddess is cradling the two figures

on her chest. But this would hardly be the case because the figures are

depicted as fallen rather than cradled.(Davison: 498) The goddess has

two birds of prey - which may be eagles or ravens - on either side of

her head. On her right shoulder is seated a small female figure, over

whose head is a lion-like animal runs. On the left side, another small

figure is holding the hair of the goddess as if plaiting her hair.

Olmsted notes that the small bird in her right hand is same as that on

the helmet on

plate

(E): both are seen from the side with a head like those of the

larger birds but with a straight beak and their almond shaped wings are

folded. Though the narrative of this scene is not known, Bergquist and

Taylor associate its iconography with

silver

phalera of Galiche; both show a female bust with a bird above each

shoulder. Since the two plates are of distinctively different style,

their claim does not seem plausible. However, they argue that both are,

nonetheless, in the same technical tradition - high repoussé silver

smithing- and in the same structure of iconography.

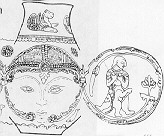

(Galiche phalera)

(Galiche phalera)

Outer Plate g

The goddess is crossing her arms on the

chest. On her right shoulder is a man struggling with a lion and on the

left is a leaping figure who is almost identical with the one on

plate

(c) and base plate. The man on the right is often associated with a

motif borrowed from the theme of Heracles and the Nemean Lion. However,

it is a widespread motif of ancient times which can be traced back

beyond classical art to Near Eastern and oriental prototypes. Bergquist

and Taylor compare this plate with that of a silver

jug

from Orlovo in south Russia. In the latter, a female face is flanked

by figures of men: the man on her right is wrestling with an animal and

the other on the left is standing alone. They also have flower blooms

around their bodies as shown on this plate. On the other hand, Olmsted

associates the head of the goddess with that on the

Marborough Vat found in Britain; he notes that the technique of

rendering the eye, nose, eye ridges, and hair is similar.

(Orlovo Jug) (Marborough Vat)

(A)

(B) (C)

(D)

(E)

(aa)

(bb)

(cc)

(dd)

(ee)

(ff)

(gg)

The proponents of the Gaulish origin put

emphasis on the Celtic motifs depicted on the cauldron such as a

horned

deity,

torques and musical instruments called

carnyx.

Most representative of all, Klindt-Jensen (1959) sees a horned deity as

Cernnunos, the Celtic god and argues that it points toward northern Gaul

as the area of its origin. However, even among those scholars who opt for

the Gaulish origin, iconographic interpretations largely vary with one

another. Instead of reading the horned figure as Cernunnos, Olmsted (1979)

suggests that it is related with the Gaulish Mercury and its Irish counter

part Cu-Chulainn. Actually Olmsted reads the whole iconography of

Gundestrup Cauldron as an illustration of a prototype Tain Bó Cuailnge,

the Irish tale. Though his interpretation is no more secure than those of

the others, Olmsted makes a notable case for the coherent narrative of the

cauldron.

Those who argue for the Gaulish origin

usually locate the cauldron in the final stage of late La tène period,

because by this time, such non Celtic elements as fantastic animals began

to appear in the diverse representations on the Celtic coinage. They also

draw analogy with other bronze cauldrons of Late La Tène period from

central and western Europe. The

Rynkeby

Cauldron which also comes from a Danish bog is the closest example to

the Gundestrup Cauldron: they are almost of the same size; both have

decorative plaques forming the interior of the upper cylindrical wall;

they share some motifs such as a human bust on the outer plates. Since the

Rynkeby Cauldron is assumed to be made around 1st century BC,

in northern or central Europe, Olmsted argues that the Gundestrup

Cauldron, like the Rynkeby Cauldron, has a La Tène III origin.

On the other hand, proponents of the eastern

view base their arguments on the cauldron’s silver smithing techniques and

its portrayal of

fantastic

animals which are commonly observed in Thracian metal work.

Powell(1971) claims the Thracian heritage by demonstrating a strong

stylistic analogy between the Gundestrup Cauldron and

Thracian

phalerae. The techniques of decorating bodies of animals with hatching

lines and punched dots are common in both. Most recently, Bergquist and

Taylor further developed his argument. By locating the cauldron in late 2nd

century BC, they claimed that silver-smithing techniques used for the

cauldron such as high repoussé, pattern punches and tracers, partial

gilding, and insetting of glass are as yet unknown from the Celtic West.

Bergquist and Taylor divide the Thracian style into two periods: earlier

style by the fourth century BC when, after Persian invasion, distinctive

and original animal style art had emerged in Thracia, and later style at

the turn of the 2nd and 1st century when the hoards

of silver vessels reappeared after two hundred years of absence. They

consider that the two styles are basically homogeneous except that in the

later style, human figures are emphasized and usually rendered in high

repoussé and they conclude that the Gundestrup Cauldron shows the traits

of both styles.

If the Cauldron was made elsewhere than

Denmark, then how did it make its way north to Jutland ? To explain its

discovery in Denmark, several options are brought up. Klindt Jensen

assumes that the cauldron was a Celtic object imported into Denmark.

Olmsted suggests that it was a war booty because the Romans employed

Germanic cavalry in Gaul. Bergquist and Taylor propose that it was made in

southeast Europe by a Thracian silver smith, possibly commissioned by

Celts (Scordisci) and transported by Cimbri who invaded the Middle lower

Danube in 120 BC and looted the Scordisci. They make conjecture that since

the cauldron takes the 4th century BC Thracian style and lacks

the Roman tradition, it was made between fourth and first century BC.

Bibliography

-

Arbman,

H., "Gundestrupkitteln- ett galliskt arbete?," Tor 20, 1948,

pp.109-116.

-

Bémont,

C., "Le Bassin de Gundestrup: remarques sur les décors végétaux,

Etudes Celtiques, vol. 16, Paris, 1979, pp. 69-99.

-

Benner

Larsen, E., "The Gundestrup Cauldron, Identification of Tool Traces,"

Iskos, vol. 5, 1985, pp. 561-74.

-

Berciu,

D., Arta traco-getica, Editura Aacademiei, Bucharest, 1969.

-

Bergquist,

A. K., and T. F. Taylor, "Thrace and Gundestrup Reconsidered,"

Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Celtic Studies,

Oxford: D. Ellis Evans, 1983, pp.268-9.

-

------------------------------, "The origin of the Gundestrup

Cauldron," Antiquity, vol. 61, 1987, pp. 10-24.

-

Bober,

J.J., "Cernunnos: Origin and Transformation of a Celtic Divinity,"

American Journal of Archeaology 55, 1951, pp13-51.

-

Davidson,

H. E., The Lost Belief of Northern Europe, 1993.

-

-------------------, "Mithraism and the Gundestrup bowl," Mithraic

Studies Vol. II (edited by John R. Hinnells), Rowman and Littlefield,

Manchester, 1975.

-

Drexel,

F., "Über den Silberkessel von Gundestrup," Jahrbuch des Kaiserlich

Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 30, 1915, pp.1-36.

-

Grosse,

R., Der Silberkessel von Gundestrup, ein Ratsel keltische Kunst,

Goetheanum, Dornach, 1963.

Hawkes, C. F. C., " Continental and British Anthropoid Weapons",

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, XXI, 1955, pp. 198-227.

-

Hawkes,

C.F.C., and M.A. Smith, "On Some Buckets and Cauldrons of the Bronze

and Early Iron Ages," Antiquity XXXVII, 1957, pp.131-98.

-

Jacobsthal, P., Early Celtic Art, Oxford, 1944.

-

Kimmig,

W., "Zur Interpretation der Opferszene auf den Gundestrup-Kessel,"

Fundberichte aus Schwaben, N.S. xvii, 1965, pp.135-43.

-

Klindt-Jensen, O., "The Gundestrup Bowl-a reassessment," Antiquity,

vol.33, pp.161-9.

-

---------------------, Gundestrupkedelen, Copenhagen, 1979

-

Laet, S.

J. and P. Lambrechts, "Traces du culte de Mithra sur le chaudron de

Gundestrup," Actes du troisième Congrès International des sociétés

pré- et protohistoriques, Zurich: City-Druck, 1950, pp. 304-6.

-

Megaw, J.

V. S., Art of the European Iron Age, Adams & Dart, Bath, 1970.

-

Meyers,

p., "Three silver objects from Thrace: a technical examination,"

Metropolitan Museum Journal 16, 1981, pp.49-54.

-

Müller,

Sophus, "Det store Slvkar fra Gundestrup i Jylland," Nordiske

Frotidsminder, I, 1892, pp.35-68.

-

-------------------, Nordische Altertumskunde, vol. 2, Strasburg,

1898.

-

Nylen, E.,

"Gundestrupkitlen och den thrakiska konsten," Tor 12, Uppsala, 1967,

pp. 133-73.

-

Olmsted,

G.S., "The Gundestrup version of Táin Bó Cuailnge," Antiquity, vol.50,

pp.95-103.

-

-----------------, The Gundestrup Cauldron, Collection Latomus, No.

162, Brussels, 1979.

-

Petersen,

E., "A Gundestrup edény és a Csórai dombormu," Archeologiai Ertesito

13, pp.199-202.

-

Piggott,

S., "The Carnyx in Early Iron Age Britain," The Antiquaries Journal

XXXIX, 1959, pp.19-32.

-

-------------, "Supplementary notes on the illustrations," The Celts

(T.G.E. Powell, 2nd ed), London: Thames & Hudson, 1980,

pp.210-217.

-

Pittioni,

R., Wer hat wann und wo den Silberkessel von Gundestrup angefertigt?

Veröffentilichungen der keltischen

-

Akademie

der Wissenschaften 3. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Asademia der

Wissenschaften, 1984.

-

Powell,

T.G.E., "From Urartu to Gundestrup: the agency of Thracian

metal-work," The European Community in Later

Prehistory, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1971.

-

Ramskou,

T., "Gundestrupterrinen," Skalk 4, 1977, p.32.

-

Reinach,

S., "À propos du vase de Gundestrup," L’Anthropologie 5, 1894,

pp.456-8.

-

--------------, "Zagreus, le serpent cornu," Revue Archéologique,

XXXV, 1899, pp.210-217.

-

--------------, "Les Carnassiers androphages dans l’art gallo-romain,"

Revue Celtique 25, 1904, pp.207-24.

-

Reinecke,

P., "Autremont und Gundestrup," Praehistorische Zeitschrift 34-5 (1),

1950, pp.361-72.

-

Rusu, M.,

"Das Keltische Fürstengrab von Ciumesti in Rumänien, Bericht der

Römisch-germanischen Kommission 50, 1969, pp.267-300.

-

Sandars,

N. K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Bartimore, 1968.

-

------------------, "Orient and Orientalizing in Early Celtic Art,"

Antiquity XLV( no.178, 1971), pp.103-112.

-

------------------, "Orient and Orientalizing: recent thoughts

reviewed," Celtic Art in Ancient Europe (C.F.C. Hawkes and

P.M. Duval ed.), London, 1976, pp.41-57.

-

Willemoes,

A., Hvad nyt om Gundestrupkarret, Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark,

Copenhagen, 1978.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gundestrup_cauldron#Interpretation

Timothy Taylor theorises that Thracian

silverworkers were an itinerant class (who he compares to present-day

Romani people) who were valued for magical and ritual services as well

as for their metalworking (itself an important ritual occupation), and

who, though living in southeastern Europe, would not have considered

themselves Thracian. He suggests they may have been a feminised caste of

men fulfilling functions of priesthood and seership, like the

Enarees of Scythia and similar groups attested across Eurasia in the

Iron Age. The figure on the cauldron typically identified with Cernunnos

is unbearded, in contrast with all the other male figures, and the similar

Mohenjo-Daro figure, though having male genitalia, is dressed in female

clothes, his posture resembling a yogic posture for channeling sexual

energy still used by a caste of Indian sorcerers.[5]

Taylor speculates that the "Cernunnos" figure, of ambiguous gender, may

have been a deity of particular importance to the Thracian silverworking

caste, part of a magical tradition common across Eurasia and still

surviving in tantric yoga and Siberian shamanism.[2]

Link:

Gundestrup cauldron

A photo of the Gundestrup cauldron

Detail of the antlered figure

depicted on plate A of the cauldron

The Gundestrup cauldron is a

richly-decorated

silver vessel, thought to date to the

1st century BC, placing it into the late

La Tène period.[1]

It was found in 1891 in a

peat bog near the hamlet of Gundestrup, in the

Aars

parish in

Himmerland,

Denmark ( 56°49′N

9°33′E

/ 56.817°N

9.55°E /

56.817; 9.55). It is now housed at

the

National Museum of Denmark in

Copenhagen. 56°49′N

9°33′E

/ 56.817°N

9.55°E /

56.817; 9.55). It is now housed at

the

National Museum of Denmark in

Copenhagen.

The Gundestrup cauldron is the

largest known example of

European Iron Age silver work (diameter 69 cm, height 42 cm).

The style and workmanship suggest

Thracian origin, while the imagery seems

Celtic. This has opened room for conflicting theories of

Thracian vs.

Gaulish

origin of the cauldron. Taylor (1991) has suggested Thracian

origin with influence by

Indian iconography.

Discovery

The cauldron was discovered by peat

cutters in a small peat-bog called Rævemose, at Gundestrup, on May

28, 1891. The Danish government paid a large reward to the

finders, who subsequently quarreled bitterly amongst themselves

over its division.[2][2][3]

The cauldron was found in a dismantled state, with five long

rectangular plates, seven short ones, one round plate (normally

termed the 'base plate') and two fragments of tubing stacked

inside the curved base. Palaeobotanical investigation of the

surrounding peat showed that the land had been dry when the

cauldron was deposited, and the peat had since gradually grown

over it. The manner of stacking suggests an attempt to make the

cauldron inconspicuous and well-hidden.[3]

Construction

The original ordering of the outer

and inner rectangular plates is uncertain, although in two places

a sharp object has apparently pierced through both an outer and an

inner plate, which can thus be aligned with some certainty. The

plates retain traces of solder, but since they seem to have been

separated by 2 cm strips of metal (now missing), rather than

soldered directly together, these traces do not help in matching

adjacent plates. One of the eight original outer plates is

missing. The circular 'base plate' originated as a

phalera, or horse's bridle decoration, and it is commonly

thought to have resided in the bottom of the bowl as a late

addition, soldered in to repair a hole.[2]

By an alternative theory, this phalera was not initially part of

the bowl, but instead formed part of the decorations of a wooden

cover.[3]

The cauldron has been repaired, and possibly even dismantled and

reassembled, multiple times, and the repair quality is inferior to

the original craftmanship.[2]

The silversmithing of the plates is

very skilled. The bowl, 70 cm across, was beaten from a single

ingot. For the relief work on the plates, the sheet-silver was

annealed to allow shapes to be beaten into high repoussé;

these rough shapes were then filled with pitch from the back to

make them firm enough for further detailing with punches and

tracers. The pitch was then melted out. Areas of pattern were

gilded, and the eyes of the larger figures were probably inset

with glass. The plates were probably worked in the flat and then

bent into curves to solder them together.[3]

Using

scanning electron microscopy Benner Larson has identified 15

different punches used on the plates, falling into three distinct

groups. No individual plate has marks from more than one of these

groups, and this fits with previous attempts at stylistic

attribution, which identify at least three different silversmiths.[3]

The plates show wear and buckling,

mostly consistent with having been forcibly torn apart at the

seams. Some of the wear may, however, hint at an even earlier

arrangement of the plates and subsequent reconstruction.[3]

Origins

For many years scholars have

interpreted the cauldron's images in terms of the Celtic pantheon.

The antlered figure in plate A has been commonly identified as

Cernunnos, and the figure holding the broken wheel in plate C

is more tentatively thought to be

Taranis. There is no consensus regarding other figures. The

elephants depicted on plate B have been explained by some

Celticists as a reference to

Hannibal's crossing of the

Alps.[2]

The silverworking techniques used in

the cauldron are unknown from the Celtic world, but are consistent

with the renowned

Thracian sheet-silver tradition; the scenes depicted are not

distinctively Thracian, but certain elements of composition,

decorative motifs and illustrated items (such as the shoelaces on

the "Cernunnos" figure) identify it as Thracian work.[3]

The silver in the cauldron cannot be

tracked to an individual mine by lead isotope analysis, since the

melted coins such artifacts are normally made of can originate in

many mines. The variety of coin used has, however, been determined

with some certainty, by careful analysis of weights: a total

weight of 9445 grams was reconstructed for the entire cauldron,

and 4255 grams for the bowl alone, and these were found to be

nearly precise integer multiples of the weight of the Persian siglos, a coin weighing 5.67 grams. By this calculation 1,666

coins were used in total, 750 of them in the bowl. This supports

an origin in Thrace, where Persian weights were in common use. The

phalera base plate, added to the cauldron at a later date, also

originated in Thrace.[2]

Depictions

Base Plate

The circular base plate depicts a

bull, above its back a female figure wielding a sword, and two

dogs, one over the bull's head, and another under its hooves.

Exterior Plates

Each of the seven exterior plates

centrally depicts a bust, probably of a deity. Plates a, b, c, and

d show bearded male figures, while the remaining three are female.

- On plate a, the bearded

figure holds in each hand a much smaller figure by the arm. Each

of those two reach upward toward a small boar. Under the feet of

the figures (on the shoulders of the god) are a dog on the left

side and a winged horse on the right side.

- The god on plate b holds in

each hand a sea-horse or dragon. In Celtic-origin theories, the

image has been associated with the Irish sea-god

Manannan.

- On plate c, a male figure

raises his empty fists. On his right shoulder is a man in a

"boxing" position, and on his left shoulder a leaping figure

with a small horseman underneath.

- Plate d shows a bearded

figure holding a stag by the hind quarters in each hand.

- The female figure on plate

e

is flanked by two smaller male busts.

- On plate f: the female

figure holds a bird in her upraised right hand. Her left arm is

horizontal, supporting a man and a dog lying on its back. She is

flanked by two birds of prey on either side of her head. Her

hair is being plaited by a small woman on the right.

- On plate g, the female

figure has her arms crossed. On her right shoulder, a scene of a

man fighting a lion is shown. On her left shoulder is a leaping

figure similar to the one on plate c.

Interior plates

Plate A:

Antlered Figure

Plate A centrally shows a horned male

figure in a seated position. In its right hand, the figure is

holding a

torc, and with its left hand, it grips a horned serpent by the

head. To the left is a stag with antlers very similar to the

humanoid. Other animals surround the scene, canine, feline,

bovine, elephant, and a human figure riding a fish or a dolphin.

The scene has been compared to a similar seal found in the

Indus Valley. In theories of Celtic origin, the figure is

often identified as

Cernunnos and occasionally as

Mercury.

In his 1928 book "Buddhism in

pre-Christian Britain" Donald Mackenzie proposed the figure was

related to depictions of the Buddha, and of the Western Buddha-god

Virupaksha.[4]

Detail of interior plate A

|

|

Plate B:

Female figure with Wheels

Plate B shows the bust of a female,

flanked by two six-spoked wheels and by mythical animals: two

elephant-like creatures and two griffins. Under the bust is a

large hound.

Plate C:

Broken Wheel

Plate C: the broken

wheel

Plate C shows the bust of a bearded

figure holding on to a broken wheel. A smaller leaping figure with

a

horned helmet also is holding the rim of the wheel. Under the

leaping figure is a horned serpent. The group is surrounded by

griffins and other creatures, some similar to those on plate

B. The wheel's

spokes

are rendered asymmetrical, but judging from the lower half, the

wheel may have had twelve spokes, which has been compared with

with

chariot burials excavated in

East Yorkshire.[citation

needed] In theories of Celtic origin the figure has

been associated with the Irish

Dagda.

Plate D:

Bull Hunting

Plate D shows a scene of

bull-slaying. Three bulls are depicted in a row, facing right.

Each bull is attacked by a man with a sword. Under the hooves of

each bull is a dog running to the right, and over the back of each

bull is a cat, also running to the right.

Plate E:

Warriors and Cauldron

Plate E: initiation ritual

In the lower half, a line of

warriors bearing spears and shields, accompanied by

carnyx players march to the left. On the left side, a large

figure is immersing a man in a cauldron. In the upper half, facing

away from the cauldron are warriors on horseback. This has been

interpreted[who?]

as an initiation scene.

Interpretation

The Gundestrup cauldron is the

largest known example of European

Iron Age silver work.

Despite the absence of any known

tradition of sheet silver

repoussé in Celtic Gaul or north-western Europe, the

decorations on the walls of the cauldron have been widely

identified with

Celtic deities and rituals. The appearance of torques around

the necks of some of the figures on the cauldron also suggest a

connection with Celtic culture. Because of these, and because of

the size of the vessel (diameter 69 cm, height 42 cm), it is said

to have been used for initiatory or sacrificial[citation

needed] purposes in

Celtic polytheism.

Bergquist and Taylor propose

manufacture by a Thracian craftsman, possibly commissioned by the

Celtic

Scordisci and fallen into the hands of the

Cimbri who invaded the Middle lower

Danube in 120 BC. Olmsted interprets the iconography as a

prototype of the

Irish myth of the

Táin Bó Cuailnge, associating the horned figure with

Cú Chulainn rather than with Cernunnos.

Timothy Taylor theorises that

Thracian silverworkers were an itinerant class (who he compares to

present-day

Romani people) who were valued for magical and ritual services

as well as for their metalworking (itself an important ritual

occupation), and who, though living in southeastern Europe, would

not have considered themselves Thracian. He suggests they may have

been a feminised caste of men fulfilling functions of priesthood

and seership, like the

Enarees of Scythia and similar groups attested across Eurasia

in the Iron Age. The figure on the cauldron typically identified

with Cernunnos is unbearded, in contrast with all the other male

figures, and the similar Mohenjo-Daro figure, though having male

genitalia, is dressed in female clothes, his posture resembling a

yogic posture for channeling sexual energy still used by a caste

of Indian sorcerers.[5]

Taylor speculates that the "Cernunnos" figure, of ambiguous gender,

may have been a deity of particular importance to the Thracian

silverworking caste, part of a magical tradition common across

Eurasia and still surviving in tantric yoga and Siberian shamanism.[2]

References

-

^ Encylopedia Britannica

[1]

-

^

a

b

c

d

e

f

g Taylor, Timothy (1992) "The

Gundestrup Cauldron" in Scientific American March 1992,

pp. 66-71.

-

^

a

b

c

d

e

f

g Bergquist, A. K. & Taylor, T.

F. (1987) "The origin of the Gundestrup cauldron" in

Antiquity Vol. 61, 1987. pp. 10-24.

-

^ "Buddhism in pre-Christian Britain", Donald A.

Mackenzie, p45

-

^ This was first pointed out by Thomas McEvilley of

Rice University, in "An Archaeology of Yoga" in Res

Vol. 1, Spring 1981, pp. 44-77.

- Kaul, F., and J. Martens,

Southeast European Influences in the Early Iron Age of Southern

Scandinavia. Gundestrup and the Cimbri,

Acta Archaeologica, vol. 66 1995, pp. 111-161.

- Klindt-Jensen, O.,

The

Gundestrup Bowl — a reassessment, Antiquity, vol. 33, pp.

161-9.

- Olmsted, G.S., The Gundestrup

version of

Táin Bó Cuailnge, Antiquity, vol. 50, pp. 95-103.

- Cunliffe, Barry (ed.),

The

Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe, NY: Oxford

University Press, 1994, 400-402.

- Green, Miranda J.,

Dictionary

of Celtic Myth and Legend. (NY: Thames and Hudson, 1992,

108-100.

See also

|

(Phalera from

Stara Zagora)

(Phalera from

Stara Zagora)

(Agighiol Vase)

(Agighiol Vase)

(Galiche phalera)

(Galiche phalera)