NORSE COSMOGONY AND COSMOLOGY

- In the following

telling, I will concentrate on the very basically Mythological; Cosmological

and Cosmological ingredients in the Norse Mythology.

(Still under

Construction)

The

Voluspa opens with the Norse account of the creation of the present

universe :

Old tales I remember | of men long ago.

I remember yet | the giants of lore [...] Of old was the age |

when Ymir lived; No Sea nor cool waves | nor sand there were; Earth had not been, | nor heaven above,

Only a yawning gap, | and

grass nowhere.

|

My Comments: What was/is in

the Universe before everything was/is created?

|

Creation and Milky Way Giants

In

the beginning there was nothing except for the ice of

Niflheim, to the north, and the fire of

Muspelheim, to the south. Between them was a yawning gap (the phrase is

sometimes left untranslated as a proper name:

Ginnungagap), and in this gap a few pieces of ice met a few sparks of

fire. The ice melted to form

Eiter, which formed the bodies of the hermaphrodite giant

Ymir and the cow

Auđumbla, whose milk fed Ymir.

Ymir fathered

Thrudgelmir, as well as two humans, one man and one woman.

Auđumbla fed by

licking the rime ice, and slowly she uncovered a man's hair. After a day,

she had uncovered his face. After another day, she had uncovered him

completely. His name was Buri.

Ginnungagap

In

Norse mythology, Ginnungagap ("magical (and creative)

power-filled space"[1])

was the vast, primordial void that existed prior to the creation of the

manifest universe.[2]

In the northern part of Ginnungagap lay the intense cold of

Niflheim, to the southern part lay the equally intense heat of

Muspelheim. The

cosmogonic process began when the effulgence of the two met in the

middle of Ginnungagap.

|

My Comments: "A power-filled

space" is related to the modern term of Cosmic Micro Wave

Background Radiation. This is a description of the 4 basically

elements of Water; Fire; Air and Soil in the Universe and how

the creation process is started.

Read

the retold Norse Creation Myth here:

Myths of

Creation |

(Cosmogony)

Cosmogony,

or cosmogeny, is any

theory concerning the coming into

existence or origin of the

universe, or about how

reality came to be. The word comes from the Greek κοσμογονία (or

κοσμογενία), from

κόσμος "cosmos, the world", and the root of

γί(γ)νομαι / γέγονα "to be born, come about". In the specialized

context of

space science and

astronomy, the term refers to theories of creation of (and study of) the

Solar System.

|

My Comments: When

mythological "theories of creation" is mentioned, it not just

concerns our Earth and the Solar System, but also our Galaxy and

beyond in the Universe. |

Cosmogony can be distinguished from

cosmology, which studies the universe at large and throughout its

existence, and which technically does not inquire directly into the source

of its origins.

|

My Comments: Mythology was

originally the 1 Story of it All without any distinctions. And

when fully understood, Mythological telling can support or even

better all other scientifically branches because of the Holistic

and Cyclic concepts in Mythology. |

The

Mythological Worlds

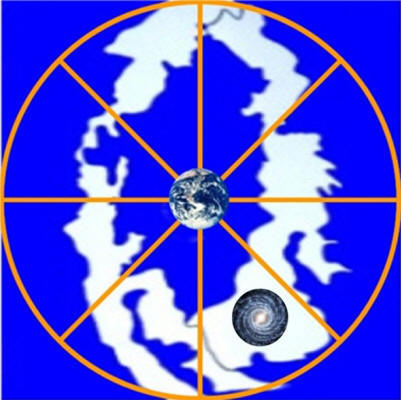

My Comments:

Before

going further in the description of the major deities, it would

be convenient to describe the Norse perception of their 3

Worlds:

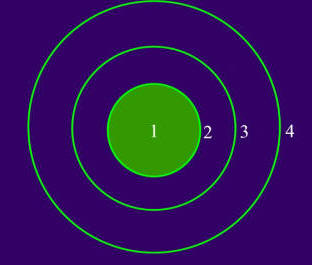

1.

Midgaard for the Humans.

2. Asgaard

for the nearer celestial day and night objects.

3. Udgaard

for the Giants in the Milky Way.

Each of

these 3 worlds or dimensions was furthermore divided in 3

"vertically" dimensions, for instants the Earth Upper, Middle

and Under hemispheres or Northern, Equatorial and Southern

hemispheres.

All these

3 Worlds also have their own 4 directional horizontal lines in

order to locate all dimensions or Worlds in the whole

mythological perception and telling of Cosmos.

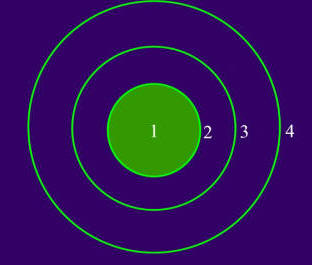

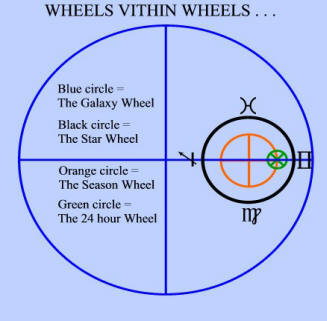

1: Midgaard for the Humans.

2: Asgaard for the nearer celestial World. 3: Udgaard for the

giant Milky Way figures and deities. 4: The extragalactic World,

the Universe, the Ginnungagap.

1: Midgaard for the Humans.

2: Asgaard for the nearer celestial World. 3: Udgaard for the

giant Milky Way figures and deities. 4: The extragalactic World,

the Universe, the Ginnungagap.

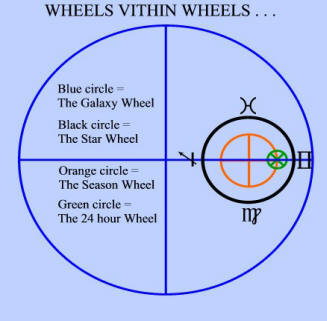

All the 3 worlds with their 4

directions, telling of the 3 world Wheels within Wheels in the

cosmological play.

(The scheme is vertically

flipped)

All the 3 worlds with their 4

directions, telling of the 3 world Wheels within Wheels in the

cosmological play.

(The scheme is vertically

flipped) |

The first Symbols of Creation

|

My Comments:

Use these schemes above and below in order to

analyse and understand your chosen favourite

religion or creative deities/creative powers.

|

|

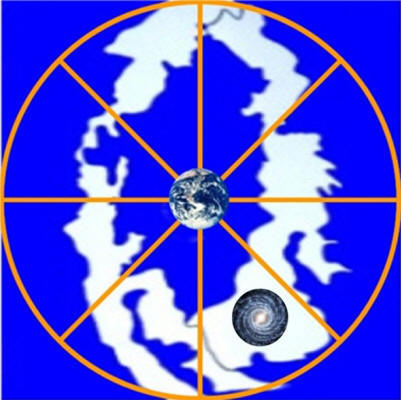

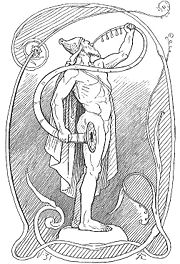

My Comments: The full

contours of our Milky Way with the left Northern hemisphere (Niflheim)

and the Southern right (Muspelheim) hemisphere. These 2 figures

is the origin for all global mythological stories of Creation.

The inserted Swirl on the

right figure marks the swirling center of our galaxy in the star

constellation of Sagittarius from where all life in the galaxy

was/is created.

The mythological stories of

Creation all tells of life created in the middle of garden Eden

from where it was "expelled" i.e. pushed out in the galactic

surrounding milky Way rivers i.e. the galactic arms.

By telling of such a movement

out from the Milky Way center, the mythological stories are

quite opposite the modern cosmology that claims that everything

is sucked inwards to the center by a "black hole".

This figure above is the most

important symbol of all human symbols as it represent the

elementary Story of Creation in connection to the specific

creation of our milky Way galaxy in where we live.

|

Mythological Keywords and

Qualities

|

NORTHERN

HEMISPHERE |

MILKY WAY GALAXY |

SOUTHERN

HEMISPHERE |

|

Male Subjects |

Creation Story

– Giants |

Female

Subjects |

|

Insert Subject

and Quality |

Gods, Goddesses

& Animals |

Insert Subject

and Quality |

|

Name |

Quality |

Anthropomorphic

Beings |

Name |

Quality |

|

Examples |

|

Ouroboros Beings |

Examples |

|

|

Odinn |

|

|

Frigg |

|

|

Jahve |

|

Ashera |

|

|

Shu |

|

Nut |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Milky Way Contours with a common Earth Pole centre. The red

“star” marks the Milky Way Centre, 29 degree Sagittarius, from where

all Creation in our Galaxy is unfolded. (Drawing of an Atlas Star

Map)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. Primary Keywords: GIANTS. Left columns: Northern

hemisphere/Male Subjects. Right

columns: Southern hemisphere/Female Subjects.

Secondary Keywords: White; Light; Primary God; Hero; Primary

Goddess; Heroin;

Animals; Anthropomorphic Beings; Airy and Winged. Omnipotent power and knowledge of

Male and Female qualities. Swirling symbols.

Opposite Figures.

Against Each other. "War against each other". Complementary stories

as well.

2.

The full Milky Way Circle is often mentioned as a Serpent or

Ouroboros, and of course the crescent Ships of North and South with its many Animals (zodiac

signs) is very well known. Okeanos or Atlantis is the Heavenly

Water; The Milky Way River; the Great Flood.

3.

Movement: The seemingly revolving figures are mythological described

as a cycle of: Rising-Flying-Diving and Dying. That is: You have to

imagine the contours in these 4 directions or positions in order to

understand the full mythological context and interactive

possibilities of the movement and the celestial objects involved in

a story.

The stories can of course goes clockwise or anticlockwise around in

the Milky Way figure above. If starting in the red centre going

clockwise, the story can be: “The heavenly Mother at the right gives

birth to a Son at the left” – and going further on to the top of the

left figure: “a man is searching for a heavenly maiden” Or, when

using the terms of “oppositional forces”: The Hero is fighting a

Dragon” . The story possibilities are endless!

4.

Dividing the full contour above in 2 halves, this gives a story

telling technique of “opposite (but complementary) forces” fighting

each other, but indeed also searching for each other. For each

others halves or cosmically Twins; for the individual Soul or

individual Twin, and of course: Searching for the Ancestral pathway

of Generations and Knowledge and for the origin of Life it self.

5.

The Creational Story Telling: From the red Swirl on the right Milky Way

figure above, everything is born and has moved out from the Galaxy

Centre. (A telling quite opposite the telling of modern Cosmology

which is wrong on this issue – nothing is contracted inwards in our

Galaxy – it’s the other way around)

The beginning of the Creation Story often takes place in the telling

of “nothing in the beginning” and goes on to tell about the very

elementary interaction between cold water and hot air and the also

interactive forces of soil, water, air and fire.

The Story of Creation often starts of when all these 6 qualities are

hit by a suddenly Light that stirs up all the clouded matter of

molecular dust and gas, creating big right- and left turning SWIRLS

that accelerates and concentrates, swallowing up all matter in a

giant melting pot and spits (explodes) it out again in a creational

discs of Suns, Planets of Matter and Gas – which later on creates

all kinds of Life – all interacting with each other because it ALL

was/is created from equal sources.

Links:

Deities all over the World:

http://native-science.net/Myths.Links.htm

John O`Neill, author of

"The night of the Gods", published in 1893: Cosmic, Cosmogonic Myths

and Symbols - Which all describes my text above and on the whole

website.

http://www.archive.org/stream/nightgods00unkngoog#page/n6/mode/1up

General Links:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmogony

|

Niflheim

Niflheimr

or Niflheim ("Mist

Home", the "Abode of Mist" or "Mist World");

being cognate with the

Old English Nifol ("dark"

and

Nebel, a German and Latin root meaning fog) is a location in

Norse mythology which overlaps with the notions of

Niflhel and

Hel. The name Niflheimr only appears in two extant sources and

they are

Gylfaginning and the much debated

Hrafnagaldr Óđins.

According to

Gylfaginning, it was one of the two primordial realms,

the other one being

Muspelheim, the realm of fire. Between these two realms of cold and

heat, creation began. Later, it became the location of

Hel, the abode of those who did not die a heroic death.

|

My Comments: When describing

the Creation as such, the old Norse used terms from the seasonal

changes on Earth and transformed the descriptions to larger

conditions in the Universe. As in almost any other old culture,

the Norse basically also divided the Earth hemisphere in 2: The

Upper World (of Niflheim) and the Underworld (of Muspelheim).

This 2 fold division could

both tell of observations of the Earth orbiting in the Solar

System, but also of the location of the Solar System in our

Milky Way Galaxy, to which the mythical story of Creation is

very close connected and described with all kind of gigantic

superlatives.

Muspelhiem becoming the

location of

Hel has nothing to do with "those who not died a heroic death". Hel is

the creative center in our galaxy in which coming Heroes and

Heroines was reborn when visiting the center of Creation and

getting knowledge of them selves; the Creation; and their

individual and collective task on the Earth.

|

Múspellsheimr

In

Norse mythology, Muspellheim ("Muspel land"), also called

Múspell, is a realm of

fire.

It is home to the fire demons or the Sons of Muspell, and

Surtr, their ruler. It is fire; and the land to the North,

Niflheim, is ice. The two mixed and created water from the melting ice

in

Ginnungagap.

|

My Comments: We have Niflheim

in the North and Muspelheim in the South. We are talking of a

Creation before the Creation. Ginnungagap is the center

in which the Creation takes place. Out of this center are the

first Giants created. As described in the Mythological Worlds

above, the Giants belongs mythological to the Milky Way contours

and therefore we are talking of a specific creation taking place

in the middle of our galaxy, the Milky Way.

|

Audhumbla

Auđumbla

(also spelled Auđumla, Auđhumbla or Auđhumla) is the

primeval cow of

Norse mythology. She is attested in

Gylfaginning, a part of

Snorri Sturluson's

Prose

Edda, in association with

Ginnungagap and

Ymir.

Auđumbla's

name appears in different variations in the manuscripts of the Prose Edda.

Its meaning is unclear. The auđ- prefix can be related to words

meaning "wealth", "ease", "fate" or "emptiness", with "wealth" being,

perhaps, the most likely candidate. The -(h)um(b)la suffix is unclear

but, judging from apparent cognates in other Germanic languages, could mean

"polled cow". Another theory links it with the name Ymir. The name

may have been obscure and interpreted differently even in pagan times.

|

My Comments: The choice of a

Cow fits very well when describing the creation in our galaxy:

There is a thundering low frequent creation sound coming from

the middle of our galaxy and the whitish galactic arms floats as

rivers of heavenly milk.

But when studying

comparative mythology,

all kinds of animals, humans and anthropomorphic beings are used

in order to describe the first physical appearances in our

galaxy.

The Milky Way center is

located on the Earth southern hemisphere in the general

direction of the Star Constellation of Sagittarius/Scorpio.

|

The Swedish scholar

Viktor Rydberg, writing in the late 19th century,

drew a parallel between the Norse

creation myths and accounts in

Zoroastrian and

Vedic mythology, postulating a common

Proto-Indo-European origin. While many of Rydberg's

theories were dismissed as fanciful by later scholars

his work on

comparative mythology was sound to a large extent.

Zoroastrian mythology does have a primeval ox which is

variously said to be male or female and comes into

existence in the middle of the earth along with

the primeval man.

|

My Comments:

Not "in the middle of the Earth" but in the

middle of our Milky Way Galaxy.

|

In

Egyptian mythology the

Milky Way, personified as the cow goddess

Hathor, was seen to be a river of milk flowing from

the udders of a heavenly cow. Hathor also has a role in

Egyptian creation myths. Due to the large distance in

time and space separating the Old Norse and Ancient

Egyptian cultures a direct connection seems unlikely.

Similar mythological themes may arise independently in

different cultures.

|

My Comments:

When observing the contours of our Milky Way no

wonder if there are global similarities in

Myths. And when taking the human spiritual

dimension in consideration, the very time

concept itself completely disappears. The

intuitive or spiritual language of genuine myths

is eternal cyclic and it deals not with linear

time concepts. |

Ymir

In

Norse mythology, Ymir, also named

Aurgelmir (Old

Norse gravel-yeller) among the giants themselves, was the founder

of the race of

frost giants and an important figure in

Norse cosmology.

|

My Comments: Ymir as a part

of "Frost Giants", shall not be interpreted as "cold beings" but

as a Giant, the first Giant appearing on the Niflheim hemisphere

in the northern celestial night Sky over the Earth. The other

minor "frost giants" mentioned in the Norse Mythology therefore

also belongs to the northern night celestial hemispheres -

either as smaller parts or details of the Milky Way contours, or

maybe as different Star Constellations in the northern celestial

night Sky. |

Snorri Sturluson combined several sources, along with some of his own

conclusions, to explain Ymir's role in the Norse creation myth. The main

sources available are the great Eddic poem

Völuspá, the question and answer poem

Grímnismál, and the question and answer poem

Vafţrúđnismál.

According to these poems,

Ginnungagap existed before Heaven and Earth. The Northern region of

Ginnungagap became full of ice, and this harsh land was known as

Niflheim.

Opposite of Niflheim was the southern region known as

Muspelheim, which contained bright sparks and glowing embers. Ymir was

conceived in Ginnungagap when the ice of Niflheim met with Muspelheim's heat

and melted, releasing "eliwaves" and drops of

eitr. The eitr drops stuck together and formed a giant of rime frost (a

hrimthurs) between the two worlds and the sparks from Muspelheim

gave him life. While Ymir slept, he fell into a sweat and conceived the race

of giants. Under his left arm grew a man and a woman, and his legs begot his

six-headed son

Ţrúđgelmir.

|

My Comments: "Eliwaves"

relates to Elivagar, the Milky Way River. For the meaning of

Eitr, se below. |

Ymir

fed from the primeval cow

Auđhumla's four rivers of milk, who in turn fed from licking the salty

ice blocks. Her licking the rime ice eventually revealed the body of a man

named

Búri. Búri fathered

Borr, and Borr and his wife

Bestla had three sons given the names

Odin,

Vili and

Vé.

|

My Comments: Se the text of

these qualities below. |

Encyclopaedia Britannica on Ymir vs. Aurgelmir: In

Norse mythology,

the first being, a giant who was created from the drops of water that formed

when the ice of

Niflheim

met the heat of

Muspelheim.

Aurgelmir was the father of all the giants; a male and a female grew under

his arm, and his legs produced a six-headed son. A cow,

Audumla,

nourished him with her milk. Audumla was herself nourished by licking salty,

rime-covered stones. She licked the stones into the shape of a man; this was

Buri,

who became the grandfather of the great god Odin and his brothers.

These gods later killed Aurgelmir, and the flow of his

blood drowned all but one frost giant. The three gods put Aurgelmir’s body

in the void,

Ginnungagap,

and fashioned the earth from his flesh,

the seas from his blood, mountains from his bones, stones from his teeth,

the sky from his skull, and clouds from his brain. Four dwarfs held up his

skull. His eyelashes (or eyebrows) became the fence surrounding

Midgard,

or Middle Earth, the home of mankind.

The

sons of Borr killed Ymir, and when Ymir fell the blood from his wounds

poured forth. Ymir's blood drowned almost the entire tribe of Frost Giants

or Jotuns. Only two jotuns survived the flood of Ymir's blood, one was

Ymir's grandson

Bergelmir (son of Ţrúđgelmir), and the other his wife. Bergelmir and his

wife brought forth new families of Jotuns.

Odin

and his brothers used Ymir's body to create

Midgard, the earth at the center of Ginnungagap. His flesh became the

earth. The blood of Ymir formed seas and lakes. From his bones mountains

were erected. His teeth and bone fragments became stones. From his hair grew

trees and

maggots from his flesh became the race of dwarfs. The gods set Ymir's

skull above Ginnungagap and made the sky, supported by four

dwarfs. These dwarfs were given the names East, West, North and South.

Odin then created winds by placing one of Bergelmir's sons, in the form of

an eagle, at the ends of the earth. He cast Ymir's brains into the wind to

become the clouds.

Next, the sons of Borr took sparks from Muspelheim and dispersed them

throughout Ginnungagap, thus creating stars and light for Heaven and Earth.

From pieces of driftwood trees the sons of Borr made men. They made a man

named Ask-ash tree and a woman named Embla-elm tree. On the brow of Ymir the

sons of Bor built a stronghold to protect the race of men from the giants.

Two

other names associated with Ymir are Brimir and Bláinn

according to Völuspá, stanza 9, where the gods discuss forming the

race of dwarfs from the "blood of Brimir and the limbs of Bláinn". Later in

stanza 37, Brimir is mentioned as having a

beer hall in

Ókólnir. In

Gylfaginning "Brimir" is the name of the hall itself, destined to

survive the destruction of

Ragnarök and providing an "abundance of good drink" for the souls of the

virtuous.

Eitr

Eitr

is a mythical substance in

Norse mythology. This

liquid substance is the origin of all living things, the first giant

Ymir was conceived from eitr. The substance is supposed to be very

poisonous and is also produced by

Jörmungandr (the Midgard serpent) and other serpents.

Etymology

The word eitr exists in most

North Germanic languages (all derived from the Old Norse language) in

Icelandic eitur, in Danish edder, in Swedish etter.

Cognates also exist in Dutch ether, in German Eiter (lit. pus),in Old Saxon

ĕttar, in Old English ăttor. The meaning

of the word is very broad: poisonous, evil, bad, angry,

sinister etc. The

word is used in common

Scandinavian folklore as a synonym for

snake poison.

|

My Comments: How can anyone

state that a life-giving substance can be poisoning, evil, bad,

angry and sinister?

They can when they confuse

the Milky Way Serpent of Creation for a physical poisonous Snake

on Earth.

So much for the etymological

analysis of the right word connected to the wrong cosmological

and mythological concept. |

Ţrúđgelmir

In

Norse mythology, Ţrúđgelmir (Old

Norse "Strength Yeller") is a

frost giant, the son of the primordial giant

Aurgelmir (who

Snorri Sturluson in

Gylfaginning identifies with

Ymir), and the father of

Bergelmir.

|

My Comments: Here we have a

discrepancy between Ymir as the first primordial Giant and

Aurgelmir. Maybe the better choice is Aurgelmir because of the

etymological connection to the Audhumbla Cow.

|

Attestations

Ţrúđgelmir appears in the poem

Vafţrúđnismál from the

Poetic Edda. When

Odin (speaking under the assumed name

Gagnrad) asks who was the eldest of the

Ćsir or of the giants in bygone days,

Vafţrúđnir answers:

"Uncountable winters

before the earth was made,

then Bergelmir was born,

Thrudgelmir was his

father,

and Aurgelmir his

grandfather."

—Vafţrúđnismál

(29)[1]

According to Rudolf Simek, Ţrúđgelmir is identical to the six-headed son

that was begotten by Aurgelmir's feet (Vafţrúđnismál, 33)[2],

but the fact that (apart from the

ţulur) he is mentioned in only one source led John Lindow to suggest

that he might have been invented by the poet[3].

Additionally, the identification of one with the other cannot be established

with certainty since, according to stanza 33, Aurgelmir had more than one

direct male offspring:

"They said that under the frost-giant's

arms (Gundestrup Cauldron Image)

a girl and boy grew together;

one foot with the other, of the wise

giant,

begot a six-headed son."[1]

Buri

Búri

was the first god in

Norse mythology. He was the father of

Borr and grandfather of

Odin.

The

meaning of either Búri or Buri is not known. The first could

be related to búr meaning "storage room" and the second could be

related to burr meaning "son". "Buri" may mean "producer."

Borr

Borr

or Burr (sometimes

anglicized Bor or Bur) was the son of

Búri and the father of

Odin in

Norse mythology. He is mentioned in the

Gylfaginning part of

Snorri Sturluson's

Prose Edda.

|

[Búri] gat son ţann er Borr er nefndr. Hann fekk ţeirar konu er

Bestla er nefnd, dóttir Bölţorns jötuns, ok gátu ţau ţrjá sonu.

Hét einn Óđinn, annarr Vili, ţriđi Vé.

Normalized Text of W |

[Búri] begat a son called Borr, who wedded the woman named

Bestla,

daughter of

Bölthorn

the giant; and they had three sons: one was Odin, the second

Vili,

the third

Vé.

Brodeur's translation |

|

Borr

is not mentioned again in the Prose Edda. In

skaldic and

eddaic poetry Odin is occasionally

referred to as Borr's son but no further information on Borr is

given. Other sources are silent.

The

role of Borr in the mythology is unclear and there is no indication that he

was worshipped in

Norse paganism.

Odin -

The Great God

Odin

(pronounced

/ˈoʊdɨn/

from

Old Norse Óđinn), is considered the chief

god in

Norse paganism. Homologous with the

Anglo-Saxon

Wōden and the

Old High German

Wotan, it is descended from

Proto-Germanic *Wōđinaz

or *Wōđanaz. The name Odin is generally accepted as the modern

translation; although, in some cases, older translations of his name may be

used or preferred. His name is related to

ōđr, meaning "fury, excitation", besides "mind", or "poetry". His

role, like many of the Norse gods, is complex. He is associated with

wisdom,

war, battle, and death, and also

magic,

poetry,

prophecy, victory, and the hunt.

Odin

was referred to by more than 200 names which hint at his various roles. He

was Known as Yggr (terror) Sigfodr (father of Victory) and Alfodr (All

Father)

[15] in the

skaldic and

Eddic traditions of

heiti and

kennings, a poetic method of indirect reference, as in a riddle.

Some epithets

establish Odin as a

father god:

Alföđr "all-father", "father of all"; Aldaföđr "father of men (or of the

age)"; Herjaföđr "father of hosts"; Sigföđr "father of victory"; Valföđr

"father of the slain".

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_names_of_Odin

Origins

The 7th century

Tängelgarda stone shows Odin

leading a troop of warriors all

bearing rings.

Valknut symbols are drawn

beneath his horse, which is

depicted with four legs.

Worship

of Odin may date to

Proto-Germanic

paganism. The

Roman historian

Tacitus may refer to Odin when he talks

of

Mercury. The reason is that, like

Mercury, Odin was regarded as

Psychopompos,"the leader of souls."

As

Odin is closely connected with a horse and

spear, and transformation/shape shifting

into animal shapes, an alternative theory of

origin contends that Odin, or at least some

of his key characteristics, may have arisen

just prior to the sixth century as a

nightmareish horse god (Echwaz), later

signified by the eight-legged

Sleipnir. Some support for Odin as a

latecomer to the Scandinavian Norse pantheon

can be found in the Sagas where, for

example, at one time he is thrown out of

Asgard by the other gods — a seemingly

unlikely tale for a well-established "all

father". Scholars who have linked Odin with

the "Death God" template include

E. A. Ebbinghaus,

Jan de Vries and

Thor Templin. The later two also link

Loki and Odin as being one-and-the-same

until the early Norse Period.

Scandinavian

Óđinn emerged from

Proto-Norse

*Wōdin during the

Migration period, artwork of this time

(on gold

bracteates) depicting the earliest

scenes that can be aligned with the High

Medieval Norse mythological texts. The

context of the new elites emerging in this

period aligns with

Snorri's tale of the indigenous

Vanir who were eventually replaced by

the

Ćsir, intruders from the Continent.[1]

Parallels between Odin and Celtic

Lugus have often been pointed out: both

are intellectual gods, commanding magic and

poetry. Both have ravens and a spear as

their attributes, and both are one-eyed.

Julius Caesar (de bello Gallico,

6.17.1) mentions Mercury as the chief god of

Celtic religion. A likely context of the

diffusion of elements of Celtic ritual into

Germanic culture is that of the

Chatti, who lived at the Celtic-Germanic

boundary in

Hesse during the final centuries before

the Common Era. (It should be remembered

that many Indo-Europeanists hypothesize that

Odin in his Proto-Germanic form was not the

chief god, but that he only gradually

replaced

Týr during the

Migration period.)

Adam of

Bremen

Written around 1080, one of the oldest

written sources on pre-Christian

Scandinavian religious practices is

Adam of Bremen's

Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum.

Adam claimed to have access to first-hand

accounts on pagan practices in

Sweden. His description of the

Temple at Uppsala gives some details on

the god.

In hoc templo, quod totum ex auro

paratum est, statuas trium deorum

veneratur populus, ita ut

potentissimus eorum Thor in medio

solium habeat triclinio; hinc et

inde locum possident Wodan et Fricco.

Quorum significationes eiusmodi sunt:

'Thor', inquiunt, 'praesidet in aere,

qui tonitrus et fulmina, ventos

ymbresque, serena et fruges gubernat.

Alter Wodan, id est furor, bella

gerit, hominique ministrat virtutem

contra inimicos. Tertius est Fricco,

pacem voluptatemque largiens

mortalibus'. Cuius etiam simulacrum

fingunt cum ingenti priapo.

-

-

Gesta

Hammaburgensis

26,

Waitz'

edition

|

In this temple, entirely decked out

in gold, the people worship the

statues of three gods in such wise

that the mightiest of them,

Thor, occupies a throne in the

middle of the chamber; Wotan and

Frikko have places on either

side. The significance of these gods

is as follows: Thor, they say,

presides over the air, which governs

the thunder and lightning, the winds

and rains, fair weather and crops.

The other, Wotan—that is, the

Furious—carries on war and imparts

to man strength against his enemies.

The third is Frikko, who bestows

peace and pleasure on mortals. His

likeness, too, they fashion with an

immense phallus.

-

-

Gesta

Hammaburgensis

26, Tschan's translation

|

|

Poetic

Edda

The sacrifice of Odin (1895) by

Lorenz Frřlich.

Völuspá

In the

poem

Völuspá, a

völva tells Odin of numerous events

reaching into the far past and into the

future, including his own doom. The Völva

describes creation, recounts the birth of

Odin by his father

Borr and his mother

Bestla and how Odin and his brothers

formed

Midgard from the sea. She further

describes the creation of the first human

beings -

Ask and Embla - by

Hśnir,

Lóđurr and Odin.

Amongst various other events, the Völva

mentions Odin's involvement in the

Ćsir-Vanir War, the self-sacrifice of

Odin's eye at

Mímir's Well, the death of his son

Baldr. She describes how Odin is slain

by the wolf

Fenrir at

Ragnarök, the subsequent avenging of

Odin and death of Fenrir by his son

Víđarr, how the world disappears into

flames and, yet, how the earth again rises

from the sea. She then relates how the

surviving Ćsir remember the deeds of Odin.

Lokasenna

In the

poem

Lokasenna, the conversation of Odin

and Loki started with Odin trying to defend

Gefjun and ended with his wife, Frigg,

defending him. In Lokasenna,

Loki derides Odin for practicing

seid (witchcraft), implying it was

women's work. Another example of this may be

found in the

Ynglinga saga where Snorri opines

that men who used seid were

ergi or

unmanly.

Hávamál

In

Rúnatal, a section of the

Hávamál, Odin is attributed with

discovering the runes. He was hung from the

world

tree,

Yggdrasil, while pierced by his own

spear for

nine

days and

nights, in order to learn the wisdom

that would give him power in the nine

worlds. Nine is a significant number in

Norse magical practice (there were, for

example,

nine

realms of existence),

thereby learning nine (later

eighteen) magical songs and eighteen

magical runes.

One of

Odin's names is Ygg, and the Norse

name for the World Ash —Yggdrasil—therefore

could mean "Ygg's (Odin's) horse". Another

of Odin's names is Hangatýr, the god

of the hanged. Sacrifices, human or

otherwise, in prehistoric times were

commonly hung in or from trees, often

transfixed by

spears[citation

needed].

Hárbarđsljóđ

Main article:

Hárbarđsljóđ

In

Hárbarđsljóđ, Odin, disguised as the

ferryman Hárbarđr, engages his son Thor,

unaware of the disguise, in a long argument.

Thor is attempting to get around a large

lake and Hárbarđr refuses to ferry him.

Prose

Edda

A depiction of Odin riding

Sleipnir from an eighteenth

century Icelandic manuscript.

Odin with his ravens and weapons

(MS

SÁM 66, eighteenth century)

Odin

had three residences in Asgard. First was

Gladsheim, a vast hall where he presided

over the

twelve Diar or Judges, whom he

had appointed to regulate the affairs of

Asgard. Second,

Valaskjálf, built of solid

silver, in which there was an elevated

place,

Hlidskjalf, from his throne on which he

could perceive all that passed throughout

the whole earth. Third was

Valhalla (the hall of the fallen), where

Odin received the

souls of the warriors killed in battle,

called the

Einherjar. The souls of women warriors,

and those strong and beautiful women whom

Odin favored, became

Valkyries, who gather the souls of

warriors fallen in battle (the

Einherjar), as these would be needed to

fight for him in the battle of

Ragnarök. They took the souls of the

warriors to Valhalla. Valhalla has five

hundred and forty gates, and a vast hall of

gold, hung around with golden shields,

and spears and coats of mail.

Odin

has a number of magical artifacts associated

with him: the spear

Gungnir, which never misses its target;

a magical gold ring (Draupnir),

from which every ninth night eight new rings

appear; and two

ravens

Huginn and Muninn (Thought

and

Memory), who fly around Earth daily and

report the happenings of the world to Odin

in Valhalla at night. He also owned

Sleipnir, an octopedal

horse, who was given to Odin by

Loki, and the severed

head of

Mímir, which foretold the future. He

also commands a pair of wolves named

Geri and Freki, to whom he gives his

food in Valhalla since he consumes nothing

but

mead or wine. From his throne,

Hlidskjalf (located in

Valaskjalf), Odin could see everything

that occurred in the

universe. The

Valknut (slain warrior's knot) is a

symbol associated with Odin. It consists of

three interlaced triangles.

Odin is an ambivalent deity. Old Norse (Viking

Age) connotations of Odin lie with

"poetry, inspiration" as well as with "fury,

madness and the wanderer." Odin sacrificed

his eye (which eye he sacrificed is unclear)

at

Mímir's spring in order to gain the

Wisdom of Ages. Odin gives to worthy poets

the

mead of inspiration, made by the dwarfs,

from the vessel Óđ-rśrir.[2]

Odin

is associated with the concept of the

Wild Hunt, a noisy, bellowing movement

across the sky, leading a host of slain

warriors.

Consistent with this,

Snorri Sturluson's

Prose Edda depicts Odin as welcoming the

great, dead warriors who have died in battle

into his hall,

Valhalla, which, when literally

interpreted, signifies the hall of the

slain. The fallen, the

einherjar, are assembled and

entertained by Odin in order that they in

return might fight for, and support, the

gods in the final battle of the end of

Earth,

Ragnarök. Snorri also wrote that Freyja

receives half of the fallen in her hall

Folkvang.

He is

also a god of war, appearing throughout

Norse myth as the bringer of victory.[citations

needed] In the

Norse sagas, Odin sometimes acts as the

instigator of wars, and is said to have been

able to start wars by simply throwing down

his spear

Gungnir, and/or sending his

valkyries, to influence the battle

toward the end that he desires. The

Valkyries are Odin's beautiful battle

maidens that went out to the fields of war

to select and collect the worthy men who

died in battle to come and sit at Odin's

table in Valhalla, feasting and battling

until they had to fight in the final battle,

Ragnarök. Odin would also appear on the

battle-field, sitting upon his eight-legged

horse

Sleipnir, with his two ravens, one on

each shoulder,

Hugin (Thought) and Munin (Memory), and

two wolves (Geri

and Freki) on each side of him.

Odin

is also associated with trickery,

cunning, and deception. Most sagas have

tales of Odin using his cunning to overcome

adversaries and achieve his goals, such as

swindling the blood of Kvasir from the

dwarves.

Prologue

Snorri Sturluson

feels compelled to give a rational account

of the Ćsir in the prologue of his Prose

Edda. In this scenario, Snorri speculates

that Odin and his peers were originally

refugees from the

Anatolian city of

Troy,

folk etymologizing

Ćsir as

derived from the word

Asia. In any case, Snorri's writing

(particularly in

Heimskringla) tries to maintain an

essentially scholastic neutrality. That

Snorri was correct was one of the last of

Thor Heyerdahl's archeoanthropological

theories, forming the basis for his

Jakten pĺ Odin. Odin was the first

of the Aesir gods in Norse Mythology. (B.K.)

Gylfaginning

"Odin's last words to

Baldr" (1908) by W.G.

Collingwood.

According to the

Prose Edda, Odin, the first and most

powerful of the Ćsir, was a son of

Bestla and

Borr and brother of

Ve and

Vili. With these brothers, he cast down

the

frost

giant

Ymir and made

Earth from Ymir's

body. The

three brothers are often mentioned

together. "Wille" is the German word for

"will" (English), "Weh" is the German word

(Gothic wai) for "woe" (English:

great sorrow,

grief, misery) but is more likely

related to the archaic German "Wei" meaning

'sacred'.

Odin

has fathered numerous children. With his

wife,

Frigg, he fathered his doomed son

Baldr and fathered the blind god

Höđr. By the personification of earth,

Fjörgyn, Odin was the father of his most

famous son,

Thor. By the giantess

Gríđr, Odin was the father of

Vídar, and by

Rinda he was father of

Váli. Also, many royal families claimed

descent from Odin through other sons. For

traditions about Odin's offspring, see

Sons of Odin.

Odin

and his brothers, Vili and Ve, are

attributed with slaying

Ymir, the Ancient Giant, to form

Midgard. From Ymir's flesh, the brothers

made the earth, and from his shattered

bones and

teeth they made the

rocks and stones. From

Ymir's

blood, they made the

rivers and

lakes. Ymir's

skull was made into the sky, secured at

four points by four dwarfs named

East,

West,

North, and

South. From Ymir's

brains, the three

Gods shaped the

clouds, whereas Ymir's eye-brows became

a barrier between Jotunheim (giant's home)

and Midgard, the place where men now dwell.

Odin and his brothers are also attributed

with making humans.

After

having made earth from Ymir's flesh, the

three brothers came across two logs (or an

ash and an

elm tree). Odin gave them breath and

life; Vili gave them brains and feelings;

and Ve gave them hearing and sight. The

first man was

Ask and the first woman was

Embla.

Odin

was said to have learned the mysteries of

seid from the

Vanic goddess and

völva

Freyja, despite the unwarriorly

connotations of using

magic.

Skáldskaparmál

"Odin with Gunnlöđ" (1901) by

Johannes Gehrts.

In

section 2 of

Skáldskaparmál, Odin's quest for

wisdom can also be seen in his work as a

farmhand for a summer, for

Baugi, and his seduction of

Gunnlod in order to obtain the

Mead of Poetry.

In

section 5 of Skáldskaparmál, the

origins of some of Odin's possessions are

described.

Sagas of

Icelanders

Ynglinga

saga

According to the

Ynglinga saga:

Odin had two brothers, the one called Ve,

the other Vili, and they governed the

kingdom when he was absent. It happened

once when Odin had gone to a great

distance, and had been so long away that

the people Of Asia doubted if he would

ever return home, that his two brothers

took it upon themselves to divide his

estate; but both of them took his wife

Frigg to themselves. Odin soon after

returned home, and took his wife back.

In

Ynglinga saga, Odin is considered the

2nd

Mythological king of Sweden, succeeding

Gylfi and was succeeded by

Njörđr.

Further, in

Ynglinga saga, Odin is

described as venturing to

Mímir's Well, near

Jötunheimr, the land of the giants; not

as Odin, but as Vegtam the Wanderer, clothed

in a dark blue cloak and carrying a

traveler's staff. To drink from the Well of

Wisdom, Odin had to sacrifice his eye (which

eye he sacrified is unclear), symbolizing

his willingness to gain the knowledge of the

past, present and future. As he drank, he

saw all the sorrows and troubles that would

fall upon men and the gods. He also saw why

the sorrow and troubles had to come to men.

Mímir

accepted Odin's eye and it sits today at the

bottom of the Well of Wisdom as a sign that

the father of the gods had paid the price

for wisdom.

Other

Sagas

"Odhin" (1901) by Johannes

Gehrts.

According to

Njáls saga:

Hjalti Skeggiason, an Icelander newly

converted to Christianity, wished to express

his contempt for the native gods, so he

sang:

-

"Ever

will I Gods blaspheme

-

Freyja methinks a dog does seem,

-

Freyja a dog? Aye! Let them be

-

Both dogs together Odin

and she!"[3]

Hjalti was found guilty of blasphemy for his

infamous verse and he ran to Norway with his

father-in-law, Gizur the White. Later, with

Olaf Tryggvason's support, Gizur and Hjalti

came back to Iceland to invite those

assembled at the

Althing to convert to Christianity

(which happened in

999).[4][5]

The

Saga of King Olaf Tryggvason,

composed around 1300, describes that

following King Olaf Tryggvason's orders, to

prove their piety, people must insult and

ridicule major heathen deities when they are

newly converted into Christianity.

Hallfređr vandrćđaskáld, who was

reluctantly converted from paganism to

Christianity by Olaf, also had to make a

poem to forsake pagan deities. Below is an

example:

-

The whole race of men to win

-

Odin's grace has wrought poems

-

(I recall the exquisite

-

works of my forebears);

-

but with sorrow, for well did

-

Viđrir's [Odin's] power please the poet,

-

do I conceive hate for the first husband

of

-

Frigg [Odin], now I serve

Christ. (Lausavísur 10, Whaley's

translation)

Flateyjarbók

_by_H._E._Freund.jpg/180px-Odin_(1825-1827)_by_H._E._Freund.jpg)

Odin (1825-1827) by H. E.

Freund.

Sörla ţáttr

is a short narrative from a later and

extended version of the Saga of Olaf

Tryggvason[6]

found in the

Flateyjarbók manuscript, which was

written and compiled by two

Christian

priests, Jon Thordson and Magnus

Thorhalson, from the late 14th[7]

to the 15th century.[8]

"Freyja was a human in Asia and was the

favorite

concubine of Odin, King of Asialand.

When this woman wanted to buy a golden

necklace (no name given) forged by four

dwarves (named Dvalinn, Alfrik, Berling, and

Grer), she offered them gold and silver but

they replied that they would only sell it to

her if she would lie a night by each of

them. She came home afterward with the

necklace and kept silent as if nothing

happened. But a man called Loki somehow knew

it, and came to tell Odin. King Odin

commanded Loki to steal the necklace, so

Loki turned into a fly to sneak into

Freyja's bower and stole it. When Freyja

found her necklace missing, she came to ask

king Odin. In exchange for it, Odin ordered

her to make two kings, each served by twenty

kings, fight forever unless some

christened men so brave would dare to

enter the battle and slay them. She said

yes, and got that necklace back. Under the

spell, king Högni and king Heđinn battled

for one hundred and forty-three years, as

soon as they fell down they had to stand up

again and fight on. But in the end, the

great Christian lord

Olaf Tryggvason arrived with his brave

christened men, and whoever slain by a

Christian would stay dead. Thus the

pagan curse was finally dissolved by the

arrival of Christianity. After that, the

noble man, king Olaf, went back to his

realm."[9]

Vili -

Brothers of Odin

In

Norse mythology, Vili and

Vé are the brothers of

Odin, sons of

Bestla daughter of

Bölţorn and

Borr son of

Búri:

Hann [Borr]

fekk ţeirar konu er Bettla hét, dóttir Bölţorns jötuns, ok fengu ţau ţrjá

sonu. Hét einn Óđinn, annarr Vili, ţriđi Vé.

Old Norse Vili means "will".

Old Norse Vé refers to a type of Germanic shrine; a

vé.

Vé -

Brothers

of Odin

In

Norse paganism, a vé is a type of

shrine or sacred enclosure. The term appears in

skaldic poetry and in place names in

Scandinavia (with the exception of

Iceland), often in connection with a Norse deity or a geographic

feature. The name of the Norse god

Vé, refers to the practice.[1]

Andy Orchard says that a vé may have surrounded a

temple or have been simply a marked, open place where worship occurred.

Orchard points out that

Tacitus, in his 1st century

CE work

Germania, says that the

Germanic peoples, unlike the

Romans, "did not seek to contain their deities within temple walls."[2]

Poetic Edda

Völuspá

In the poem

Völuspá, a

völva tells Odin of numerous events reaching into the

far past and into the future, including his own doom. The

Völva describes creation, recounts the birth of Odin by his

father

Borr and his mother

Bestla and how Odin and his brothers formed

Midgard from the sea. She further describes the creation

of the first human beings -

Ask and Embla - by

Hśnir,

Lóđurr and Odin.

Amongst various other

events, the Völva mentions Odin's involvement in the

Ćsir-Vanir War, the self-sacrifice of Odin's eye at

Mímir's Well, the death of his son

Baldr. She describes how Odin is slain by the wolf

Fenrir at

Ragnarök, the subsequent avenging of Odin and death of

Fenrir by his son

Víđarr, how the world disappears into flames and, yet,

how the earth again rises from the sea. She then relates how

the surviving Ćsir remember the deeds of Odin.

Lokasenna

In the poem

Lokasenna, the conversation of Odin and Loki started

with Odin trying to defend

Gefjun and ended with his wife, Frigg, defending him. In

Lokasenna,

Loki derides Odin for practicing

seid (witchcraft), implying it was women's work. Another

example of this may be found in the

Ynglinga saga where Snorri opines that men who used

seid were

ergi or

unmanly.

Hávamál

In Rúnatal, a

section of the

Hávamál, Odin is attributed with discovering the

runes. He was hung from the world

tree,

Yggdrasil, while pierced by his own spear for

nine

days

and

nights, in order to learn the wisdom that would give him

power in the nine worlds. Nine is a significant number in

Norse magical practice (there were, for example,

nine realms of existence), thereby learning nine (later

eighteen) magical songs and eighteen magical runes.

One of Odin's names is

Ygg, and the Norse name for the World Ash —Yggdrasil—therefore

could mean "Ygg's (Odin's) horse". Another of Odin's names

is Hangatýr, the god of the hanged. Sacrifices, human

or otherwise, in prehistoric times were commonly hung in or

from trees, often transfixed by

spears.

Hárbarđsljóđ

Main article:

Hárbarđsljóđ

In Hárbarđsljóđ,

Odin, disguised as the ferryman Hárbarđr, engages his son

Thor, unaware of the disguise, in a long argument. Thor is

attempting to get around a large lake and Hárbarđr refuses

to ferry him.

Frigg

- the Great Goddess

"Frigga Spinning the

Clouds" "Frigga Spinning the

Clouds"

The

asterism

Orion's Belt was known as "Frigg's

Distaff/spinning

wheel" (Friggerock) or "Freyja's Distaff" (Frejerock)[6].

Some have pointed out that the constellation is on the celestial equator and

have suggested that the stars rotating in the night sky may have been

associated with Frigg's spinning wheel[7].

Frigg's name means "love" or "beloved one" (Proto-Germanic *frijjō, cf.

Sanskrit priyā "dear woman") and was known among many northern European

cultures with slight name variations over time: e.g. Friggja in Sweden, Frīg

(genitive

Frīge) in Old English, and

Fricka in

Richard Wagner's operatic cycle

Der Ring des Nibelungen.[8]

Modern English translations have sometimes altered Frigg to Frigga,

presumably to avoid the English vulgarism

frig. It has been suggested that "Frau

Holle" of

German folklore is a survival of Frigg.[9]

Frigg's hall in Asgard is

Fensalir, which means "Marsh Halls."[10]

This may mean that marshy or boggy land was considered especially sacred to

her but nothing definitive is known. The goddess

Saga, who was described as drinking with Odin from golden cups in her

hall "Sunken Benches," may be Frigg by a different name.[11]

Frigg was a goddess associated with married women. She was called up by

women to assist in giving birth to children, and Scandinavians used the

plant

Lady's Bedstraw (Galium verum) as a sedative, they called it

Frigg's grass)[6].

Frigg's

grass. Frigg's

grass.

Frigg

(sometimes anglicized as Frigga) is a major goddess in

Norse paganism, a subset of

Germanic paganism. She is said to be the wife of

Odin, and is the "foremost among the goddesses" and the queen of Asgard.[1]

Frigg appears primarily in

Norse mythological stories as a wife and a mother. She is also described

as having the power of prophecy yet she does not reveal what she knows.[2]

Frigg is described as the only one other than Odin who is permitted to sit

on his high seat

Hlidskjalf and look out over the universe. The English term Friday

derives from the

Anglo-Saxon name for Frigg, Frigga.[3]

In

Norse mythology, Hliđskjálf (sometimes

Anglicized Hlidskjalf; from

hlid "side, gate" or hlifd

"protection", and skjalf "shelf, bench, plane"[1])

is the high seat of

Odin enabling him to see into all worlds.

Frigg's children are

Baldr and

Höđr, her stepchildren are

Thor,

Hermóđr,

Heimdall,

Tyr,

Vidar,

Váli, and

Skjoldr. Frigg's companion is

Eir, a goddess associated with medical skills. Frigg's attendants are

Hlín,

Gná, and

Fulla.

In

the

Poetic Edda poem

Lokasenna 26, Frigg is said to be

Fjörgyns mćr ("Fjörgynn's

maiden"). The problem is that in Old Norse mćr means both "daughter"

and "wife", so it is not fully clear if Fjörgynn is Frigg's father or

another name for her husband

Odin, but

Snorri Sturluson interprets the line as meaning Frigg is Fjörgynn's

daughter (Skáldskaparmál

27), and most modern translators of the Poetic Edda follow Snorri. The

original meaning[dubious

–

discuss] of

fjörgynn was the earth, cf. feminine

version

Fjorgyn, a byname for Jörđ, the earth.[4]

Etymology

Main

article:

Frijjō

*Frijjō

("Frigg-Frija"),

cognate to

Sanskrit

Priya, is the name or epithet of a

Common Germanic

love goddess, the most prominent female member of the

*Ansiwiz

(gods), and often identified as the spouse of the chief god, *Wōdanaz

(Woden-Odin).

The two

Old Norse goddesses

Freyja and

Frigg appear to be reflected by only a single goddess in

West Germanic and likely derive from a single

Common Germanic goddess, one of whose epithets was

*frijjō

"beloved" and *frawjō

"lady". Freyja "Lady" is thus considered a hypostasis of the chief "Frigg-Frija"

goddess, together with other hypostases like

Fulla and

Nanna derived from

skaldic epithets, similar to

Odhr besides

many other aspects in skaldic tradition deriving from

Odin.

Old

Norse Frigg (genitive Friggjar),

Old Saxon Fri, and

Old English Frig are derived from

Common Germanic Frijjō.[5]

Frigg is cognate with

Sanskrit prīyā́

which means "wife".[5]

The root also appears in Old Saxon fri which means "beloved lady", in

Swedish as fria ("to propose for marriage") and in Icelandic as

frjá which means "to love".[5]

Eir -

Friig´s Companion

Frigg's companion is

Eir In

Norse mythology, Eir (Old

Norse "help, mercy"[1])

is a

goddess and/or

valkyrie associated with medical skill. Eir is attested in the

Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional

sources; the

Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by

Snorri Sturluson; and in

skaldic poetry, including a

runic inscription from

Bergen,

Norway from around 1300. Scholars have theorized about whether or not

these three sources refer to the same figure, and debate whether or not Eir

may have been originally a healing goddess and/or a

valkyrie. In addition, Eir has been theorized as a form of the goddess

Frigg and has been compared to the

Greek goddess

Hygiea.

Frigg's

Attendants

Hlín

In

Norse mythology, Hlín (Old

Norse "protectoress"[1])

is a

goddess associated with the goddess

Frigg. Hlín

appears in a poem in the

Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional

sources, the

Prose

Edda, written in the 13th century by

Snorri Sturluson, and in

kennings found in

skaldic

poetry. Hlín has been theorized as possibly another name for Frigg.

In the Poetic Edda

poem

Völuspá, Hlín receives a mention regarding the

foretold death of the god

Odin during the immense battle waged at

Ragnarök:

- Then is

fulfilled Hlín's

- second

sorrow,

- when Óđinn

goes

- to fight with

the wolf,

- and

Beli's

slayer,

- bright,

against

Surtr.

- Then shall

Frigg's

- sweet friend

fall.[2]

In chapter 35 of the

Prose Edda book

Gylfaginning, Hlín is cited twelfth among a series

of sixteen goddesses.

High tells

Gangleri (earlier in the book described as King

Gylfi in disguise) that Hlín "is given the function of

protecting people whom Frigg wishes to save from some

danger." High continues that, from this, "someone who

escapes finds refuge (hleinar)."[3]

In chapter 51, the above mentioned Völuspá stanza is

quoted.[4]

In chapter 75 of the book

Skáldskaparmál Hlín appears within a list of 27

ásynjur names.[5]

In

skaldic poetry, the name Hlín is frequent in

kennings for women. Examples include

Hlín hringa

("Hlín of rings"), Hlín gođvefjar ("Hlín of velvet")

and arm-Hlín ("arm-Hlín"). The name is already used

frequently in this way by the 10th-century poet

Kormákr Ögmundarson and remains current in skaldic

poetry through the following centuries, employed by poets

such as

Ţórđr Kolbeinsson,

Gizurr Ţorvaldsson and

Einarr Gilsson.[6]

The name remained frequently used in woman kennings in

rímur poetry, sometimes as

Lín.[7]

In a verse in

Hávarđar saga Ísfirđings, the phrase

á Hlín fallinn

("fallen on Hlín") occurs. Some editors have emended the

line[8][9]

while others have accepted the reading and taken Hlín to

refer to

the

earth.[10]

Gná

In

Norse mythology, Gná is a

goddess who runs errands in

other worlds for the goddess

Frigg and

rides the flying, sea-trodding horse Hófvarpnir (Old

Norse "he who throws his

hoofs about",[1]

"hoof-thrower"[2]

or "hoof kicker"[3]).

Gná and Hófvarpnir are attested in the

Prose

Edda, written in the 13th century by

Snorri Sturluson. Scholarly theories have been proposed about Gná as a

"goddess of fullness" and as potentially cognate to

Fama from

Roman mythology. Hófvarpnir and the eight-legged steed

Sleipnir

have been cited examples of transcendent horses in Norse mythology.

In chapter 35 of the

Prose Edda book

Gylfaginning, the enthroned figure of

High provides brief descriptions of 16

ásynjur. High lists Gná thirteenth, and says that Frigg

sends her off to different worlds to run errands. High adds

that Gná rides the horse Hófvarpnir, and that this horse has

the ability to ride through the air and atop the sea.[3]

High continues that "once some

Vanir saw her path as she rode through the air" and that

an unnamed one of these Vanir says, in verse:

- "What flies

there?

- What fares

there?

- or moves

through the air?"[4]

Gná responds in verse,

in doing so providing the parentage of Hófvarpnir; the

horses

Hamskerpir and Garđrofa:

- "I fly not

- though I fare

- and move

through the air

- on Hofvarpnir

- the one whom

Hamskerpir got

- with Gardrofa."[4]

The source for these

stanzas is not provided and they are otherwise unattested.

High ends his description of Gna by saying that "from Gna's

name comes the custom of saying that something gnaefir

[looms] when it rises up high."[4]

In the Prose Edda book

Skáldskaparmál, Gná is included among a list of 27

ásynjur names.[5]

Fulla

In

Germanic mythology, Fulla (Old

Norse, possibly "bountiful"[1])

or Volla (Old

High German) is a

goddess. In

Norse mythology, Fulla is described as wearing a golden

snood and as tending to the

ashen box and the footwear owned by the goddess

Frigg, and,

in addition, Frigg confides in Fulla her secrets. Fulla is attested in the

Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional

sources; the

Prose

Edda, written in the 13th century by

Snorri Sturluson; and in

skaldic

poetry. Volla is attested in the "Horse Cure"

Merseburg Incantation, recorded anonymously in the 10th century in

Old High German, in which she assists in healing the wounded

foal of Phol

and is referred to as Frigg's sister. Scholars have proposed theories about

the implications of the goddess.

Poetic Edda

In the prose

introduction to the Poetic Edda poem

Grímnismál, Frigg makes a wager with her husband—the

god

Odin—over the hospitality of their human patrons. Frigg

sends her servant maid Fulla to warn the king

Geirröd—Frigg's patron—that a magician (actually Odin in

disguise) will visit him. Fulla meets with Geirröd, gives

the warning, and advises to him a means of detecting the

magician:

-

Henry Adams Bellows translation:

- Frigg

sent her handmaiden, Fulla, to Geirröth. She

bade the king beware lest a magician who was

come thither to his land should bewitch him,

and told this sign concerning him, that no

dog was so fierce as to leap at him.[2]

|

-

Benjamin Thorpe translation:

- Frigg

sent her waiting-maid Fulla to bid Geirröd

be on his guard, lest the

trollmann who was coming should do him

harm, and also say that a token whereby he

might be known was, that no dog, however

fierce, would attack him.[3]

|

|

Prose Edda

In chapter 35 of the

Prose Edda book

Gylfaginning,

High provides brief descriptions of 16

ásynjur. High lists Fulla fifth, stating that, like the

goddess

Gefjun, Fulla is a

virgin, wears her hair flowing freely with a gold band

around her head. High describes that Fulla carries Frigg's

eski, looks after Frigg's footwear, and that in Fulla

Frigg confides secrets.[4]

In chapter 49 of Gylfaginning, High details that, after the death of the

deity couple

Baldr and

Nanna, the god

Hermóđr wagers for their return in the underworld

location of

Hel.

Hel, ruler of the location of the same name, tells

Hermóđr a way to resurrect Baldr, but will not allow Baldr

and Nanna to leave until the deed is accomplished. Hel does,

however, allow Baldr and Nanna to send gifts to the living;

Baldr sends Odin the ring

Draupnir, and Nanna sends Frigg a robe of linen, and

"other gifts." Of these "other gifts" sent, the only

specific item that High mentions is a finger-ring for Fulla.[5]

The first chapter of

the Prose Edda book

Skáldskaparmál, Fulla is listed among eight ásynjur

who attend an evening drinking banquet held for

Ćgir.[6]

In chapter 19 of Skáldskaparmál, poetic ways to refer

to Frigg are given, one of which is by referring to her as

"queen [...] of Fulla."[7]

In chapter 32, poetic expressions for

gold are given, one of which includes "Fulla's

snood."[8]

In chapter 36, a work by the

skald

Eyvindr skáldaspillir is cited that references Fulla's

golden snood ("the falling sun [gold] of the plain

[forehead] of Fulla's eyelashes shone on [...]").[9]

Fulla receives a final mention in the Prose Edda in

chapter 75, where Fulla appears within a list of 27 ásynjur

names.[10]

Frigg´s Son and Stepsons

Baldr

Balder is a

god in

Norse Mythology associated with light and beauty.

In the 12th century, Danish accounts

by

Saxo Grammaticus and other Danish Latin chroniclers recorded a

euhemerized account of his story. Compiled in

Iceland

in the 13th century, but based on much older

Old Norse poetry, the

Poetic Edda and the

Prose

Edda contain numerous references to the death of Baldr as both a great

tragedy to the

Ćsir

and a harbinger of

Ragnarök.

According to

Gylfaginning, a book of

Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda, Baldr's wife is

Nanna and their son is

Forseti.

In Gylfaginning, Snorri relates that Baldr had the greatest ship ever

built, named

Hringhorni, and that there is no place more beautiful than his hall,

Breidablik.

Poetic Edda

_by_H._E._Freund.jpg/180px-Mímer_and_Balder_Consulting_the_Norns_(1821-1822)_by_H._E._Freund.jpg)

"Mímer

and Balder Consulting the Norns"

(1821-1822) by

H. E. Freund.

In the

Poetic Edda the tale of Baldr's death is

referred to rather than recounted at length.

Among the visions which the

Völva sees and describes in the prophecy

known as the

Völuspá is one of the fatal mistletoe,

the birth of

Váli and the weeping of

Frigg (stanzas 31-33). Yet looking far into

the future the Völva sees a brighter vision of a

new world, when both Höđr and Baldr will come

back (stanza 62). The Eddic poem

Baldr's Dreams mentions that Baldr has

bad dreams which the gods then discuss.

Odin rides to Hel and awakens a seeress, who

tells him Höđr will kill Baldr but Vali will

avenge him (stanzas 9, 11).

Prose Edda

Baldr's death is portrayed in this

illustration from an 18th century

Icelandic manuscript.

In Gylfaginning, Baldur is described as

follows:

-

Annar sonur Óđins er

Baldur, og er frá honum gott ađ

segja. Hann er svá fagr álitum ok

bjartr svá at lýsir af honum, ok

eitt gras er svá hvítt at jafnat er

til Baldrs brár. Ţat er allra grasa

hvítast, ok ţar eptir máttu marka

fegrđ hans bćđi á hár og á líki.

Hann er vitrastr ása ok fegrst

talađr ok líknsamastr. En sú náttúra

fylgir honum at engi má haldask dómr

hans. Hann býr ţar sem heita

Breiđablik, ţat er á himni. Í ţeim

stađ má ekki vera óhreint[.][2]

|

-

The second son of

Odin is Baldur, and good things are

to be said of him. He is best, and

all praise him; he is so fair of

feature, and so bright, that light

shines from him.

A certain herb is so white that

it is likened to Baldr's brow; of

all grasses it is whitest, and by it

thou mayest judge his fairness, both

in hair and in body. He is the

wisest of the Ćsir, and the

fairest-spoken and most gracious;

and that quality attends him, that

none may gainsay his judgments. He

dwells in the place called

Breidablik, which is in heaven; in

that place may nothing unclean be[.]

— Brodeur's translation[3]

|

|

Apart from

this description Baldr is known primarily for

the story of his death. His death is seen as the

first in the chain of events which will

ultimately lead to the destruction of the gods

at

Ragnarok. Baldr will be reborn in the new

world, according to

Völuspá.

He had a

dream of his own death and his mother had the

same dreams. Since dreams were usually

prophetic, this depressed him, so his mother

Frigg made every object on earth

vow never to hurt Baldr. All objects made

this vow except

mistletoe.[4]

Frigg had thought it too unimportant and

nonthreatening to bother asking it to make the

vow (alternatively, it seemed too young to

swear).

"Odin's last words to Baldr" (1908)

by W. G. Collingwood.

When

Loki, the mischief-maker, heard of this, he

made a magical spear from this plant (in some

later versions, an arrow). He hurried to the

place where the gods were indulging in their new

pastime of hurling objects at Baldr, which would

bounce off without harming him. Loki gave the

spear to Baldr's brother, the blind god

Höđr, who then inadvertently killed his

brother with it (other versions suggest that

Loki guided the arrow himself). For this act,

Odin and the giantess

Rindr gave birth to

Váli who grew to adulthood within a day and

slew Höđr.[5]

Baldr was ceremonially burnt upon his ship,

Hringhorni, the largest of all ships. As he was

carried to the ship, Odin whispered in his ear.

This was to be a key riddle asked by Odin (in

disguise) of the giant

Vafthrudnir (and which was, of course,

unanswerable) in the poem

Vafthrudnismal. The riddle also appears

in the riddles of

Gestumblindi in

Hervarar saga.[6]

The dwarf

Litr was kicked by

Thor into the funeral fire and burnt alive.

Nanna, Baldr's wife, also threw herself on the

funeral fire to await Ragnarok when she would be

reunited with her husband (alternatively, she

died of grief). Baldr's horse with all its

trappings was also burned on the pyre. The ship

was set to sea by

Hyrrokin, a

giantess, who came riding on a wolf and gave

the ship such a push that fire flashed from the

rollers and all the earth shook.

"Balder the Good" by Jacques Reich.

Upon

Frigg's entreaties, delivered through the

messenger

Hermod,

Hel promised to release Baldr from the

underworld if all objects alive and dead would

weep for him. And all did, except a

giantess,

Ţökk, who refused to mourn the slain god.

And thus Baldr had to remain in the underworld,

not to emerge until after Ragnarok, when he and

his brother Höđr would be reconciled and rule

the new earth together with Thor's sons.

When the

gods discovered that the

giantess Ţökk had been

Loki in disguise, they hunted him down and

bound him to three rocks. Then they tied a

serpent above him, the venom of which dripped

onto his face. His wife

Sigyn gathered the venom in a bowl, but from

time to time she had to turn away to empty it,

at which point the poison would drip onto Loki,

who writhed in pain, thus causing earthquakes.

He would free himself, however, in time to

attack the gods at Ragnarok.

Höđr

(often anglicized as Hod[1])

is the brother of

Baldr in

Norse mythology. Guided by

Loki he shot

the

mistletoe missile which was to slay the otherwise invulnerable Baldr.

According to the

Prose

Edda and the

Poetic Edda the goddess

Frigg made

everything in existence swear never to harm Baldr, except for the mistletoe

which she found too young to demand an oath from. The gods amused themselves

by trying weapons on Baldr and seeing them fail to do any harm.

Loki, upon

finding out about Baldr's one weakness, made a missile from mistletoe, and

helped Höđr shoot it at Baldr. After this

Odin and the

giantess

Rindr gave

birth to

Váli who grew to adulthood within a day and slew Höđr.

The

Danish

historian

Saxo Grammaticus recorded an alternative version of this myth in his

Gesta Danorum. In this version the mortal hero

Hřtherus and

the demi-god Balderus compete for the hand of

Nanna. Ultimately Hřtherus slays Balderus.

The Prose Edda

In the

Gylfaginning part of

Snorri Sturluson's

Prose Edda Höđr is introduced in an ominous way.

|

Höđr

heitir einn ássinn, hann er blindr. Śrit er hann

styrkr, en vilja mundu gođin at ţenna ás ţyrfti eigi

at nefna, ţvíat hans handaverk munu lengi vera höfđ

at minnum međ gođum ok mönnum.

-

Eysteinn Björnsson's edition |

"One of the

Ćsir is named Hödr: he is blind. He is of

sufficient strength, but the gods would desire that

no occasion should rise of naming this god, for the

work of his hands shall long be held in memory among

gods and men." -

Brodeur's translation |

|

Höđr is not mentioned

again until the prelude to Baldr's death is described. All

things except the mistletoe (believed to be harmless) have

sworn an oath not to harm Baldr, so the Ćsir throw missiles

at him for sport.

|

En Loki tók

mistiltein ok sleit upp ok gekk til ţings. En Höđr

stóđ útarliga í mannhringinum, ţvíat hann var blindr.

Ţá mćlti Loki viđ hann: "Hví skýtr ţú ekki at Baldri?"

Hann svarar: "Ţvíat ek sé eigi hvar Baldr er, ok ţat

annat at ek em vápnlauss." Ţá mćlti Loki: "Gerđu ţó

í líking annarra manna ok veit Baldri sśmđ sem ađrir

menn. Ek mun vísa ţér til hvar hann stendr. Skjót at

honum vendi ţessum."

Höđr tók

mistiltein ok skaut at Baldri at tilvísun Loka.

Flaug skotit í gögnum hann ok fell hann dauđr til

jarđar. Ok hefir ţat mest óhapp verit unnit međ

gođum ok mönnum. -

Eysteinn Björnsson's edition |

"Loki took the

mistletoe and pulled it up and went to the

Thing. Hödr stood outside the ring of men,

because he was blind. Then spake Loki to him: 'Why

dost thou not shoot at Baldr?' He answered: 'Because

I see not where Baldr is; and for this also, that I

am weaponless.' Then said Loki: 'Do thou also after

the manner of other men, and show Baldr honor as the

other men do. I will direct thee where he stands;

shoot at him with this wand.'

Hödr took

mistletoe and shot at Baldr, being guided by Loki: